Zeinab Saleh - Art Now

Tate Britain - Millbank

Until 23rd June, 2024

An essay by Estelle Simpson

Within Zeinab Saleh’s distinct style, a technique aligns her with many of today’s most popular painters. It was walking back from the Tate Britain I was caught considering why more fluid, watery methods have become emblematic of modern painting. Contemporaries such as Peter Doig are coined with its development, as thereafter this manner of layering paint seems to have become a mystifying influence on a generation of art makers who embrace the fantastical expression or shifty, unreliability achieved with cascading paint washes. Further, this extra slippery impressionism is so typically applied to everyday minutiae. It turns out, that many identify with the ‘escapist’ opportunities offered by ‘Magic Realism’, a genre which aligns itself with the features exhibited in these artworks. What does the appeal of this style say about its audiences? Why are translucent drippy washes becoming the trademark of the rising cohort of painters today? How does this link to a growth in escapist tendencies and a heightened identification with symptoms of trauma? I aim to extrapolate on the cloudiness many figurative paintings seem to accomplish today.

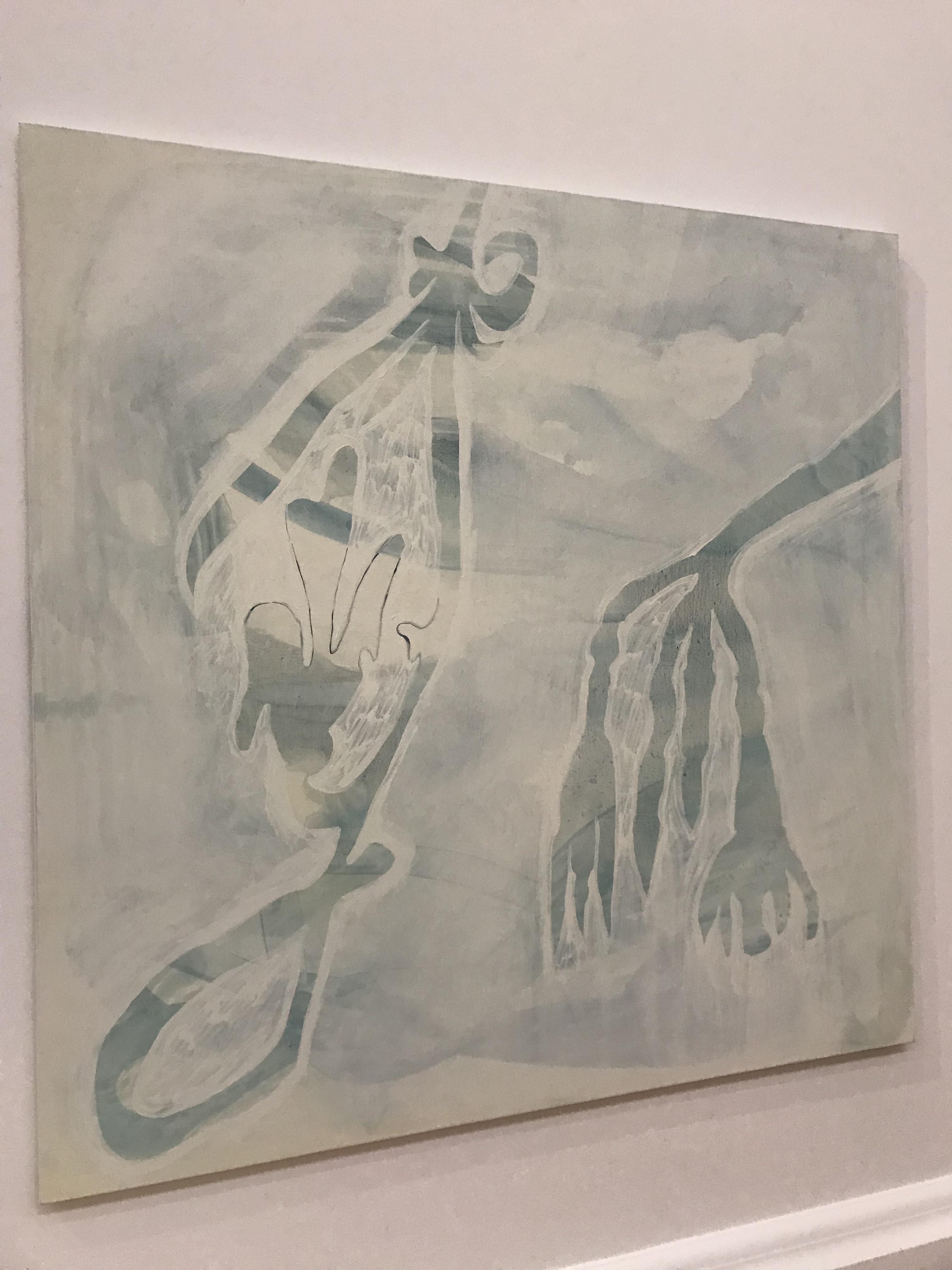

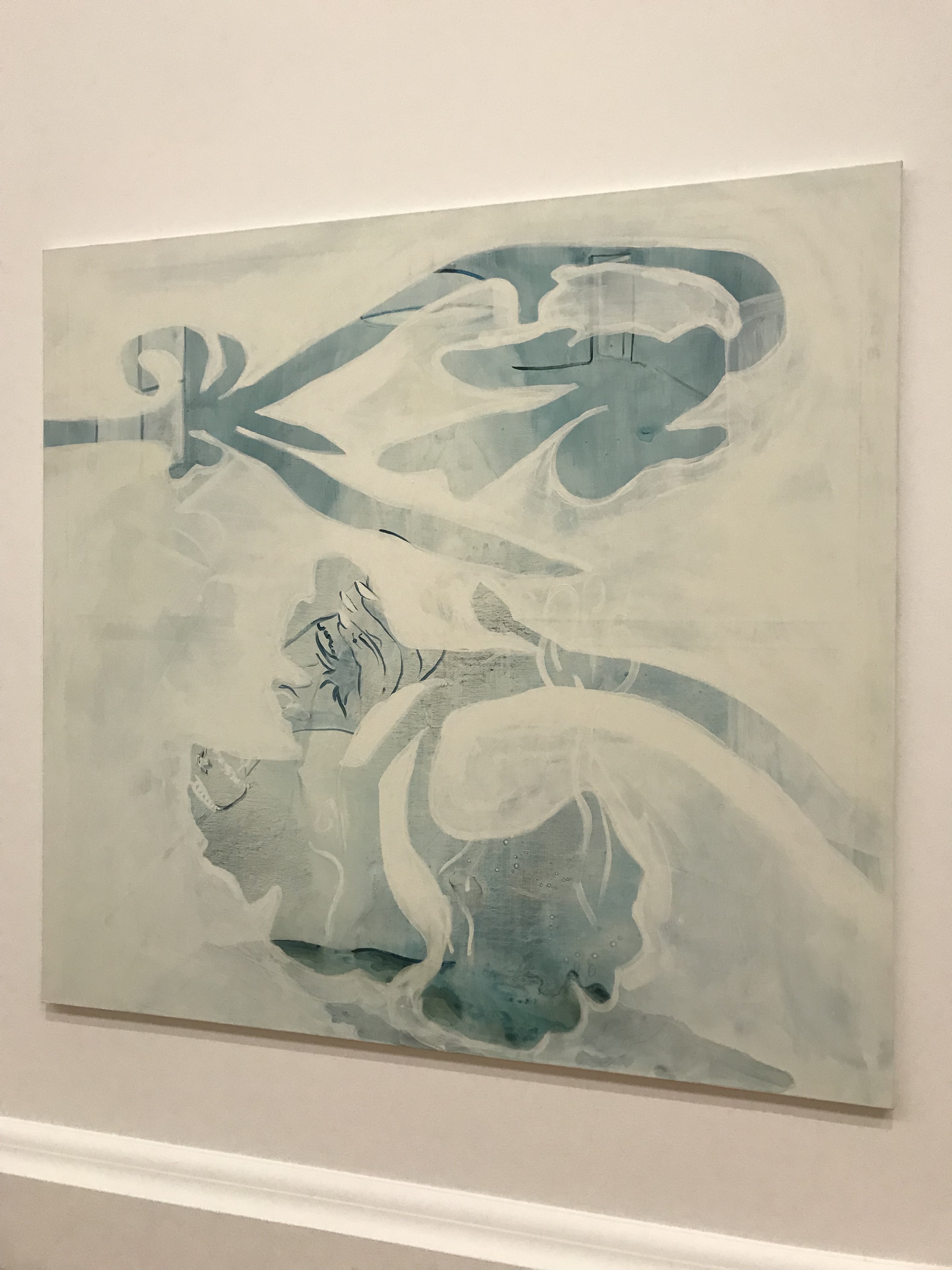

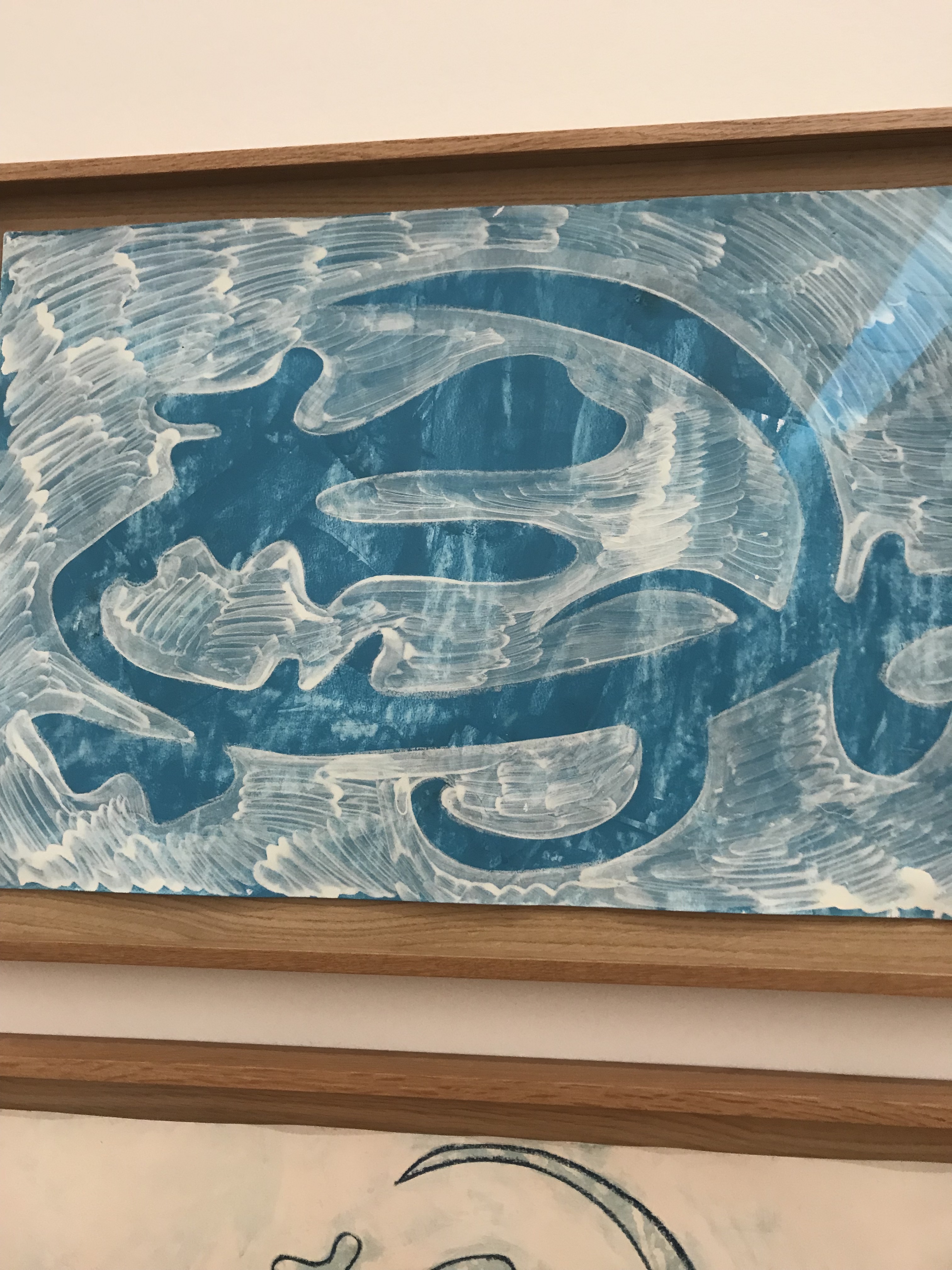

Galleries are often places I retreat, to flee from the outside stresses of life for a little time. In these places, the paintings often help pull me out of the monotony and into a beautiful extratemporal abyss. When observing art, it provides something to look at that distracts – it is an escape from time that keeps me returning to these places. Specific paintings really facilitate this experience, with Zeinab Saleh’s room in the Tate Britain providing a breath-taking place of calm and tranquillity. Saleh provides visual sanctuaries, utilising the seamless possibilities of transparency. For instance, boasting a multi-layered approach, veneers on top of the translucent preliminary room compositions are barely opaque, allowing these frames to naturally suffuse into the image. Therefore, an effortlessly appealing bond occurs between the materiality and form of indoor spaces, and the natural vivacity of plant forms layered on top. Providing a cropped lens, aspects of lifeless interiors exist just under diaphanous layers as familiar spaces are drenched by a dreamy template of organic references. Scenes are disassociated from reality, as ghostly shadows provide spaces of quietness to explore inner desires, ambitions, vulnerabilities, and fears. Freed from a sense of time or place, these formations of inky washes, charcoal, acrylic paint, and soft pastel encourage slow looking through cryptic interplay of ambiguous natural shapes. Overall, Saleh’s room at the Tate is a beguiling refuge.

Paintings today seem to mirror the increasing attraction of escapism; there is a heightened allure in resorting to wishful tendencies. The role of modern communication means we are hyper-aware of problems within the world that don’t directly affect us - such as climate change, political challenges and chaos, pandemics and epidemics, disinformation… to name a few. While we are more exposed to information, we may want to distract ourselves from, we are also living in a time where there is an immeasurable abundance of ways to facilitate this need for escapism in our fingertips: video games, virtual realities, TV and media, movies, and music. Often these methods, given we are more informed of uncertainties within our world, are lifelines which allow for a maintenance of a semblance of peace. Modern modes of communication lead to a feeling of being trapped, lamenting the increasingly dreary state of our existence, and thus, we are finding any way possible to escape this in socially acceptable ways. As helpless voyeurs through screens, magic realism alters the unfavourable into something bearable, a spell cast to erase the pain for a moment. It also is a style which the artist can explore darker themes with more lucidity and obscurity through a digestible metaphorical narrative.

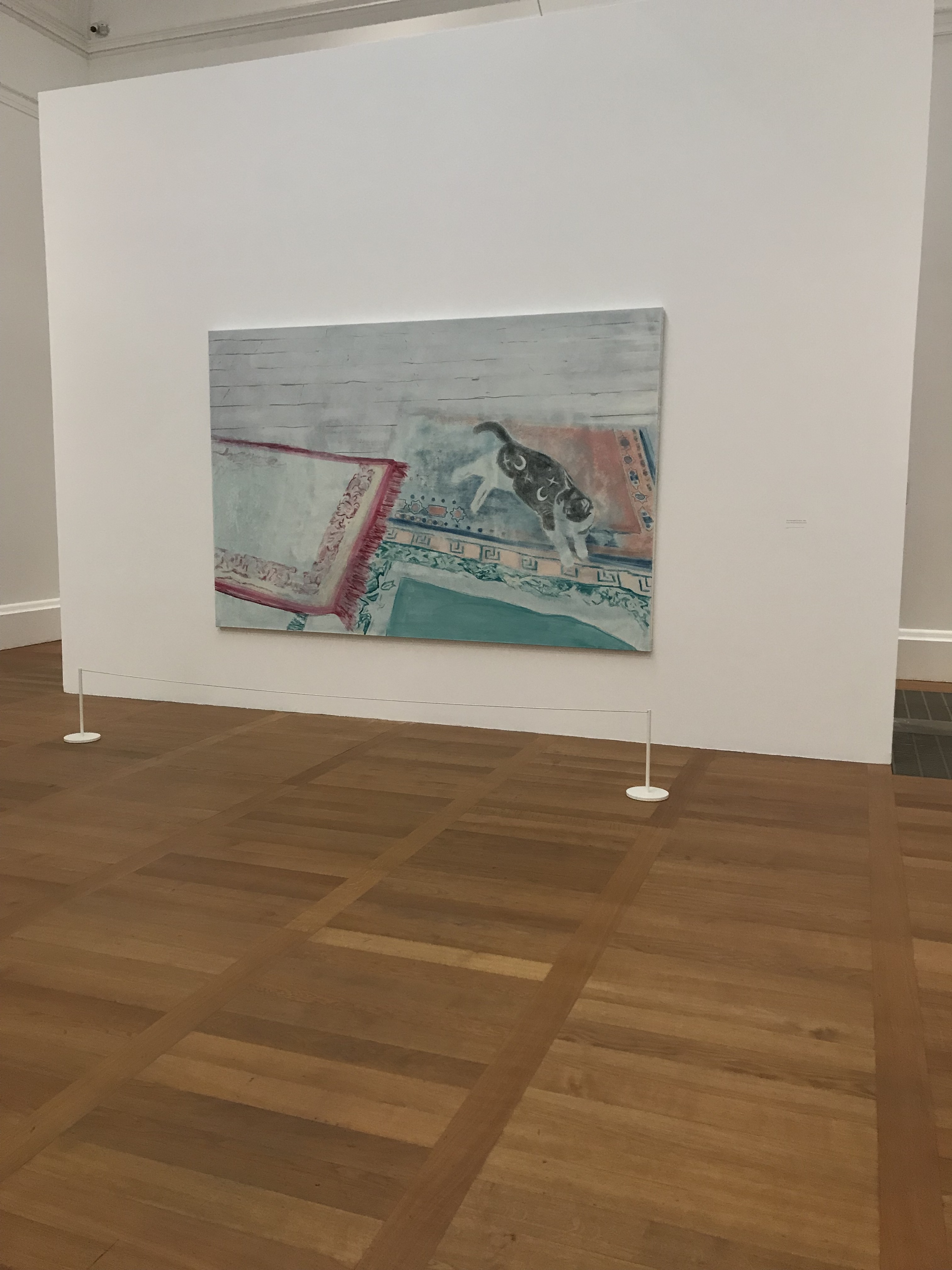

In many forms of art there has been a resurgence of ‘magic realism’, a genre which facilitates this escapism whilst being firmly rooted in our collective world. Within impressions of disconnected realities, it is possible to find moments of peace within the mundane which in the ‘real world’ seems harder and harder to experience. Understanding the world through fantastical elements seems to be a humanising and purifying mode, driving home moral and universal lessons. Or, for many interpretations in painting, resorting to an exploration of human’s relationship with nature, which creates a focus on the fundamental urges which align us as a collective. For example, in Cranston’s paintings he often involves animal subjects which are expressed with the mysticism they elicit when confronted with the idea that, as pets, they share our spaces but are ultimately different from our human consciences; pets exist in our domestic territories but are loaded in their own manner than a person figure. These ruminations on intrinsic psychologies and simple connections with nature we all share breaks down the barriers by highlighting what draws us together as vulnerable and complex beings. These themes are so broad and wide-reaching that they can connect with many audiences, revealing emotions and needs many of us are united by. Therefore, making us feel less alone.

The magic realism involved in these paintings also permits a place to find tranquillity amidst the chaos. Reality is given a veneer of hazy, dreaminess which makes it more digestible, or draws attention to more appealing effigies of the everyday. It may be a contributor to the popularisation of the likes of painters such as Doig, whose post-modern impressions provide the mesmerising and beguiling interpretations of landscapes that are a gateway to this kind of whimsical, disassociated reality. This style of painting, involving acidic washes and offering distorting perspectives of scenes seems to be reflected in a generation of painter’s today, such as Mohammed Saleh and Hurvin Anderson. Cranston, a student of Doig, also replicates this in powerfully serene paintings. Cranston has mastered rarified atmospheres through similar fragmented hues and thinly rendered presences found in Doig’s paintwork. In many of Cranston’s pieces, reality is diluted by a sense of cosmic shock, as the pleasant, intimate vignettes of daily life are imbued with a radioactive glow. The painters in the contemporary engage more with concerns of the present rather than reproducing historical images or mythological scenes. The desired effect of the artist is to render the story-telling involved in recalling distant memories; the natural exaggerations or misremembering involved in hindsight perspectives are portrayed in each works visual twisting of actuality. There seems to be more of a desire to explore the feelings elicited by environments through expression and less on factual rendering.

Escapist art does not just focus on the dreamlike. Often, exploring nightmarish imagery allows contemporary artists to work through lacerations of the past. In the genre, often ordinary settings are warped to speak of elements of social-political and cultural commentary. For example, Sami approaches themes of war inflicting on the memories of the home environment through unstable interiors and impressions of reality infused with the uncanny. The surrealism invested in these pieces makes the everyday more vividly incomprehensible, reflecting the challenges associated with the past, and how they overshadow the artist’s memories. While the paintings are an instrument for exploring the belated response to trauma surfacing in memories since Sami sook refuge, the metaphorical representation of war and violence within familiar places such as the home and cityscapes highlights the proximity of threat the artist recalls. The magical realism applied acts as a bridge between interpretations of everyday vistas and the feelings and emotions elicited from hindsight. This allows the artist to inject real places with a sense of memories and trauma through imagining the everyday expressed in a fantastical way. In some works, focus on small details that are expressed with an intense sense of mystery or illusion, illustrates how Sami utilises the genre within even the minutia of daily life, demonstrating the huge impact of these experiences in even the most normal areas of life.

Perhaps, it’s a new relationship with the language of trauma that may have contributed to this popularisation of the expressive painting style as a genre exploring the emotions and memories associated with the everyday. ‘Trauma’ started to trend as a hashtag on TikTok from the early 2020’s whilst ’The Body Keeps the Score’ - a complex account on trauma and PTSD - was a significant success during lockdown, indicating something profound about the national psyche. It shows the breadth of people focusing on their ‘traumas’, discerning the heightened generalisation of the term, and therefore this makes artwork depicting the symptoms associated with this mental illness highly appealing. It seems more people identify with the characteristics of PTSD whether diagnosable or not; patterns picked up on are: a tendency to superimpose the traumatic experience on to everything around them or an inability to decipher what is going on around them. These symptoms can also be observed in the Doig mystery, where references to real life are made unrecognisable due to their fluid surfaces, reflecting the traces of trauma left behind on places or things. Sami’s complicated compositions impart memory of pain onto the mundane, demonstrating an oeuvre stipulated with an army of metaphors. For instance, ‘The Prayer Room’ presents a forlorn plant casting a threatening shadow, reflecting the way those with trauma deposit the feelings associated with the events onto their surroundings. The genre of magic realism encapsulates the surreal and uncanny overshadowing reality, becoming the manifestation of what it is like to live with PTSD as an illness in which life becomes unfamiliar and confusing, obscured by a shroud of distressing memories. Painters who use magic realism to express real life fraught with these distortions of pain and internal suffering become greatly identifiable to audiences searching to not feel so alone in their anguish.

In the same way Sami contorts everyday objects, such as a plant, mattress, or mirror – as well as drawing on the perplexing or deceptive possibilities of light and shadow – Saleh also presents a perplexing use of silhouettes. She pulls on illusion to make real things less decipherable mirroring the baffling or confusing. In the painting ‘No Shoes Inside’ 2024, the spectral shape of a snake emerges from the corner of the canvas. Elsewhere, what might first appear as the outline of a flower’s stem suddenly recalls a menacing skeletal hand or a river spreading across a landscape. Shape and motif become less reliable. Yet, a purity envelops the room in this exhibition highlight, giving it cathartic potential. In this way, Magic realism also offers the same escapism which those with trauma turn to to manage or relieve themselves from pain. Painting is ultimately another form of media which provides comfort, entertainment, and something to relate to.

The bottom line: when magic realism is employed to create nightmarish realities, these painters describe the world around us in a way that mirrors our own fears and repulsions. As when it is utilised to impart dreamy qualities onto existence, it makes life more alluring, or renews a sense of optimism and interest in normality.

The undeniable resurgence of ‘magic realism’ is observed in the willingness of audiences to engage with mystical interpretations of history, and of life itself, rather than holding these depictions to the standards of ‘rationality’ of archival documents. This receptivity to the warping of reality demonstrates we are more attuned to excepting illusion, and more willing to step outside of our physical reason for a second. Reading a magic realist painting means opening oneself up to being moved by the myriad of emotions elicited, and actively accepting the supernatural presented for what it is.