‘Too Many Reflections’

June, 2025

To render the female body as a woman is a way of thinking about the historical exclusion of emotion in figural studies previously created by male painters, delving into psychological experiences in a more tropological sense. I am fired by stories, at once alerted to women’s suffering. A window of perception into the nuances of psychological distress have been offered in literary texts such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, the lesser acknowledged 19th century critique of ‘The Victorian Chaise-Longue’ by Marghanita Laski, and, more recently, Amapro Davila’s contemporary short stories collection: ‘The Houseguest.’ Being guided through the narrator's and characters' mental states, these writers explore the home as a site of danger, oppression, and sinister possibilities. This is further pronounced in the painterly achievements of Paula Rego’s body of works approaching quotidian fears, or the heavy emotions, vulnerability, and trauma woven into Louise Bourgeois’ oeuvre. The lived experience of a mental health condition can find one feeling unmoored and alone in the world, yet both the making and consumption of these uncompromising visions has been a vital tool in alleviating this for me, and, more universally, vitally prompts a greater empathy towards these states of being in society.

![]()

My body of paintings set my own chilling experience in conversation with that of Gillman’s narrator or Rego’s ‘Dog Woman’ as the intimate, domestic spaces which are supposed to make you feel safe turn out to be the most terrifying of all. The approach, informed by these artists and writers alike, is not to make a spectacle of such fears, but achieve impressions of how these lesions are formed in unsuspecting places; that they exist in the most mundane places of all is what is so debilitating to everyday life. In fact, monsters are not residing under the bed, or skeletons hidden in the closets, what is haunting in actuality are the very objects themselves.

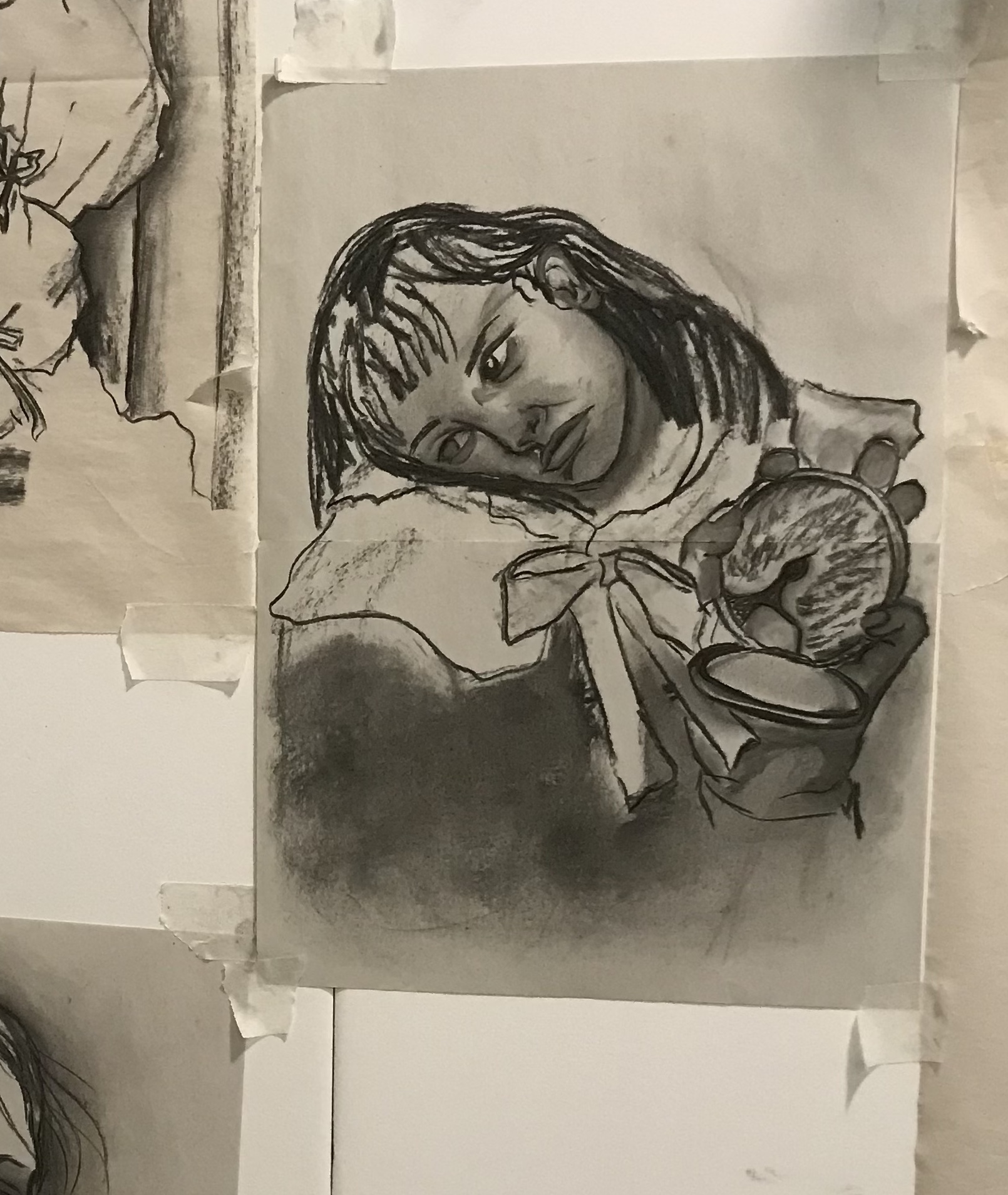

Rego comments “Making a painting can reveal things you keep secret from yourself,’ resonating with my own intuitive process of making which post creation unmasks traumas and truths I have avoided directly confronting in personal life. An encounter recently with my current paintings in the studio saw me addressed by a host of mirror impressions. Wall length, compact, table standing - unknowingly, in these various forms employed in intention to complement compositions and guide attention, I had rendered in each piece a reflective surface. Akin to the haunting presence of a garish yellow wallpaper to Gillman’s young mother, this eerie infiltration of the mirror had interrupted the space I had tried to convalesce in.

![]()

Honestly, the mirror has fed into my psyche in a fiendish and deceiving way since my formative years in dance, an everyday object which has taken on terrifying significance to me later in life. My own seclusion in my psychological reckoning with the mirror led me to create a reality of my body image which constantly shifted, laden with flaws, and ultimately disorientated how I felt about myself. This is a condition known as ‘body dysmorphia’. I found that Laski articulates such a disturbance of not recognising the vessel one resides in aptly in Melanie’s confusion “there came a new dread, or an old fear long endured and known,” demonstrating the incongruous nature of the unknown, combined with an eerie familiarity. In the environment which provided me with such a release and strength to express myself, I was met with conflictions, “not the touch of soft pink wool, but the harsh rough strangeness.” In dance studios lined with reflective panels, these walls are meant to provide vital functionality in being able to assess one's posture and coordination to achieve an ideal form. Unfortunately, this early attention to observation can lead to a hindering preoccupation with a striving for perfection within the image of the body that is impossible to be satisfied with.

I seek to eschew direct representations of dance, portraying images that explore the infiltrations of this practice beyond the studio. Early exposure to the art of somatic posture and form, as well as expressing embodied emotion through physical movement - a meticulous process of performing strength and elegance - foreshadowed the complex layers of memory and feelings that characterise my painting now. In this case, my odes and reckonings to this present themselves in my compositions in more complex symbolism that I hope offers narratives that are at once intimate and universally resonate. Louise Bourgeois championed this stitching together of personal history and universal themes. I recall ‘The Arch of Hysteria’ which aptly engages with the titled state of beings historical and psychoanalytical connotations, confronting misconception. Bourgeois’s works always feel like a vital reminder of the strength in vulnerability, and her ability to express assertiveness but sensitivity in her artwork is bolstered by personal experience, in the orbit of doctors and psychologists researching mental illness. She successfully portrayed the realistic depths of hysteria at a time when many surrealists were romanticizing such conditions and usurping clinical photography of patients as a form of “poetic discovery,” which results in artwork that idealises them. For Bourgeois, hysteria isn’t a wonder, but a fact of life, a reminder one is alive; the fascination in a subject is equalled by a respectful handling of its nuances.

I don’t hate the mirror. I really enjoy pulling out my table standing mirror to perform the daily ritual of applying make up. This is therapeutic to me. It functions in facilitating me applying my mask to feel I can face the outside world, or adding a bow to my hair on the days I need extra thrill to face. Yet the relationship with the reflective object is more nuanced and complex than this, and at other moments its presence is less desired, even tormenting. It is once apparent that mirrors have been around all of time, at the very basic level the reflective surface of water. As Davila’s short stories delve into situations characters are trapped within as a result of the proximity of their fears to normal life, brutality is manifested into the everyday. I paint the surrounding settings of figures in an animated representation, making static ornaments flutter with the same thrill or threat of a character's inner world. This ambience of entrapment is significant in Davila’s prose, asserting that whatever the exterior threats are posed towards characters, these are ultimately physical manifestations of inner paranoias and phobias, and what is inescapable is one’s own mind. Hence, this helps me understand that it is not the mirror itself, but the way my interaction with it has been formed, and the infiltrations of past memory associated with reflectivity that arise when I engage with them.

The figures themselves exhibit a gaze that ostensibly gives off a deep introspection, yet an additional layer of complexity is inferred from the sense of distance that a viewer would experience, finding them ‘looking through’ their audience. Often, ill feeling felt daily becomes mundane, tedious, and I think of Davilas comment on the ambiguity of such expressions of daily suffering appearing as “the gaze of an abandoned dog or the colour of a ghost.”

![]()

Similarly to how mental illness is misinterpreted or dismissed, the effects of BDD can often be conflated with one being too vain, in my own experience, rejecting the seriousness of the disorder. Yet this misunderstanding can result in a deeper spiral into conditions such as depression or self-harm, or neglect a serious flag of other OCD symptoms. Whilst estimates suggest 1-2% of the population struggle from BDD, I believe this percentage seems wildly unreflective of its prevalence, perhaps due to masses of unreported cases. In sharing my thoughts through expression, I would like to make such despairing states less taboo or stigmatised, even more identifiable for others. Each reflective surface in my compositions fails to mirror or obscures any reference to a human figure, asserting that the distress is felt beyond that of the bodily impression and concern for one’s appearance. The gothic narrative angles of my paintings suggest a sinister lens under the surface level embellishments of portable accessories or wall hangings, giving an exploration into the inherent panic of the domestic. In a sense, what may be a functional accessory ostensibly, has become an accessory to trauma and physical distress.

During an ongoing period of convalescence, I have sought to remove the mirror from permanent display in my home environment in an attempt to overcome such traumas related to the body.

My practice explores the paradox that women my age can feel, growing up in a society where gender is rapidly evolving whilst having been instilled with traditional gender stereotypes by those who raised us.

June, 2025

To render the female body as a woman is a way of thinking about the historical exclusion of emotion in figural studies previously created by male painters, delving into psychological experiences in a more tropological sense. I am fired by stories, at once alerted to women’s suffering. A window of perception into the nuances of psychological distress have been offered in literary texts such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’, the lesser acknowledged 19th century critique of ‘The Victorian Chaise-Longue’ by Marghanita Laski, and, more recently, Amapro Davila’s contemporary short stories collection: ‘The Houseguest.’ Being guided through the narrator's and characters' mental states, these writers explore the home as a site of danger, oppression, and sinister possibilities. This is further pronounced in the painterly achievements of Paula Rego’s body of works approaching quotidian fears, or the heavy emotions, vulnerability, and trauma woven into Louise Bourgeois’ oeuvre. The lived experience of a mental health condition can find one feeling unmoored and alone in the world, yet both the making and consumption of these uncompromising visions has been a vital tool in alleviating this for me, and, more universally, vitally prompts a greater empathy towards these states of being in society.

My body of paintings set my own chilling experience in conversation with that of Gillman’s narrator or Rego’s ‘Dog Woman’ as the intimate, domestic spaces which are supposed to make you feel safe turn out to be the most terrifying of all. The approach, informed by these artists and writers alike, is not to make a spectacle of such fears, but achieve impressions of how these lesions are formed in unsuspecting places; that they exist in the most mundane places of all is what is so debilitating to everyday life. In fact, monsters are not residing under the bed, or skeletons hidden in the closets, what is haunting in actuality are the very objects themselves.

Rego comments “Making a painting can reveal things you keep secret from yourself,’ resonating with my own intuitive process of making which post creation unmasks traumas and truths I have avoided directly confronting in personal life. An encounter recently with my current paintings in the studio saw me addressed by a host of mirror impressions. Wall length, compact, table standing - unknowingly, in these various forms employed in intention to complement compositions and guide attention, I had rendered in each piece a reflective surface. Akin to the haunting presence of a garish yellow wallpaper to Gillman’s young mother, this eerie infiltration of the mirror had interrupted the space I had tried to convalesce in.

Honestly, the mirror has fed into my psyche in a fiendish and deceiving way since my formative years in dance, an everyday object which has taken on terrifying significance to me later in life. My own seclusion in my psychological reckoning with the mirror led me to create a reality of my body image which constantly shifted, laden with flaws, and ultimately disorientated how I felt about myself. This is a condition known as ‘body dysmorphia’. I found that Laski articulates such a disturbance of not recognising the vessel one resides in aptly in Melanie’s confusion “there came a new dread, or an old fear long endured and known,” demonstrating the incongruous nature of the unknown, combined with an eerie familiarity. In the environment which provided me with such a release and strength to express myself, I was met with conflictions, “not the touch of soft pink wool, but the harsh rough strangeness.” In dance studios lined with reflective panels, these walls are meant to provide vital functionality in being able to assess one's posture and coordination to achieve an ideal form. Unfortunately, this early attention to observation can lead to a hindering preoccupation with a striving for perfection within the image of the body that is impossible to be satisfied with.

I seek to eschew direct representations of dance, portraying images that explore the infiltrations of this practice beyond the studio. Early exposure to the art of somatic posture and form, as well as expressing embodied emotion through physical movement - a meticulous process of performing strength and elegance - foreshadowed the complex layers of memory and feelings that characterise my painting now. In this case, my odes and reckonings to this present themselves in my compositions in more complex symbolism that I hope offers narratives that are at once intimate and universally resonate. Louise Bourgeois championed this stitching together of personal history and universal themes. I recall ‘The Arch of Hysteria’ which aptly engages with the titled state of beings historical and psychoanalytical connotations, confronting misconception. Bourgeois’s works always feel like a vital reminder of the strength in vulnerability, and her ability to express assertiveness but sensitivity in her artwork is bolstered by personal experience, in the orbit of doctors and psychologists researching mental illness. She successfully portrayed the realistic depths of hysteria at a time when many surrealists were romanticizing such conditions and usurping clinical photography of patients as a form of “poetic discovery,” which results in artwork that idealises them. For Bourgeois, hysteria isn’t a wonder, but a fact of life, a reminder one is alive; the fascination in a subject is equalled by a respectful handling of its nuances.

I don’t hate the mirror. I really enjoy pulling out my table standing mirror to perform the daily ritual of applying make up. This is therapeutic to me. It functions in facilitating me applying my mask to feel I can face the outside world, or adding a bow to my hair on the days I need extra thrill to face. Yet the relationship with the reflective object is more nuanced and complex than this, and at other moments its presence is less desired, even tormenting. It is once apparent that mirrors have been around all of time, at the very basic level the reflective surface of water. As Davila’s short stories delve into situations characters are trapped within as a result of the proximity of their fears to normal life, brutality is manifested into the everyday. I paint the surrounding settings of figures in an animated representation, making static ornaments flutter with the same thrill or threat of a character's inner world. This ambience of entrapment is significant in Davila’s prose, asserting that whatever the exterior threats are posed towards characters, these are ultimately physical manifestations of inner paranoias and phobias, and what is inescapable is one’s own mind. Hence, this helps me understand that it is not the mirror itself, but the way my interaction with it has been formed, and the infiltrations of past memory associated with reflectivity that arise when I engage with them.

The figures themselves exhibit a gaze that ostensibly gives off a deep introspection, yet an additional layer of complexity is inferred from the sense of distance that a viewer would experience, finding them ‘looking through’ their audience. Often, ill feeling felt daily becomes mundane, tedious, and I think of Davilas comment on the ambiguity of such expressions of daily suffering appearing as “the gaze of an abandoned dog or the colour of a ghost.”

Similarly to how mental illness is misinterpreted or dismissed, the effects of BDD can often be conflated with one being too vain, in my own experience, rejecting the seriousness of the disorder. Yet this misunderstanding can result in a deeper spiral into conditions such as depression or self-harm, or neglect a serious flag of other OCD symptoms. Whilst estimates suggest 1-2% of the population struggle from BDD, I believe this percentage seems wildly unreflective of its prevalence, perhaps due to masses of unreported cases. In sharing my thoughts through expression, I would like to make such despairing states less taboo or stigmatised, even more identifiable for others. Each reflective surface in my compositions fails to mirror or obscures any reference to a human figure, asserting that the distress is felt beyond that of the bodily impression and concern for one’s appearance. The gothic narrative angles of my paintings suggest a sinister lens under the surface level embellishments of portable accessories or wall hangings, giving an exploration into the inherent panic of the domestic. In a sense, what may be a functional accessory ostensibly, has become an accessory to trauma and physical distress.

During an ongoing period of convalescence, I have sought to remove the mirror from permanent display in my home environment in an attempt to overcome such traumas related to the body.

My practice explores the paradox that women my age can feel, growing up in a society where gender is rapidly evolving whilst having been instilled with traditional gender stereotypes by those who raised us.