Rossetti’s

Tate Britain - Chelsea

th August - 24th September

By Estelle Simpson

Unfortunately, what was eulogized as ‘revolutionary’ was lost for me in the cinnamon swirls of lurid characters. An exhibition promising the “daring” and “radical” seemed misleading, portraying what I saw relfected as the Rossetti’s ‘brotherhood’ and a fixation with their flirtings with objectified pre-Raphelite muses. Confined within heavily-worked canvases are peaky stunners staring out towards the viewer with sultry, pouting gazes. The show may have been celebratory of its exquisite beauties - but who are they? One man’s fairytale sees their true lives concealed between shiny rouge lips. These paintings were as wan as Ophelia’s macarbre body floating on the river in which they echoed. This show displays Dante’s gaze predominently and should be credited seedy rather than subervise. Claims of the insurgent family felt messy, and the true story of torment, guilt and grief remain a tangle, hidden under fiery tresses of rich red hair.

Firstly you are introduced into a room filled with murmers of Christina’s poetry facilitated by some clever sensor-orientated technology. Yet this seems to be the only curatorial success of a show in which you will have to reach the final two rooms to experience the most noteworthy works. Her dramatic prose haunts the room with an intensity of feeling and emotion captured with exquisite, painful precision. An established, significant voice of her time, this highlights her powerful poetry which had an influence on her brothers work. Yet, it seems her masterpieces were translated creepily into the Brotherhood’s canvases which fed on a handful of muses. Despite a brief overview of Christina and Liz, these ladies quickly become folklore in the exhibition which swiftly forgets their prolific creative output. Even the Virgin in Dante’s 1882 recreation of ‘The Annunciation’ seems to recoil awkwardly; displayed in the first room, her disturbed presence seems to forebode the trend of the rest of the exhibition.

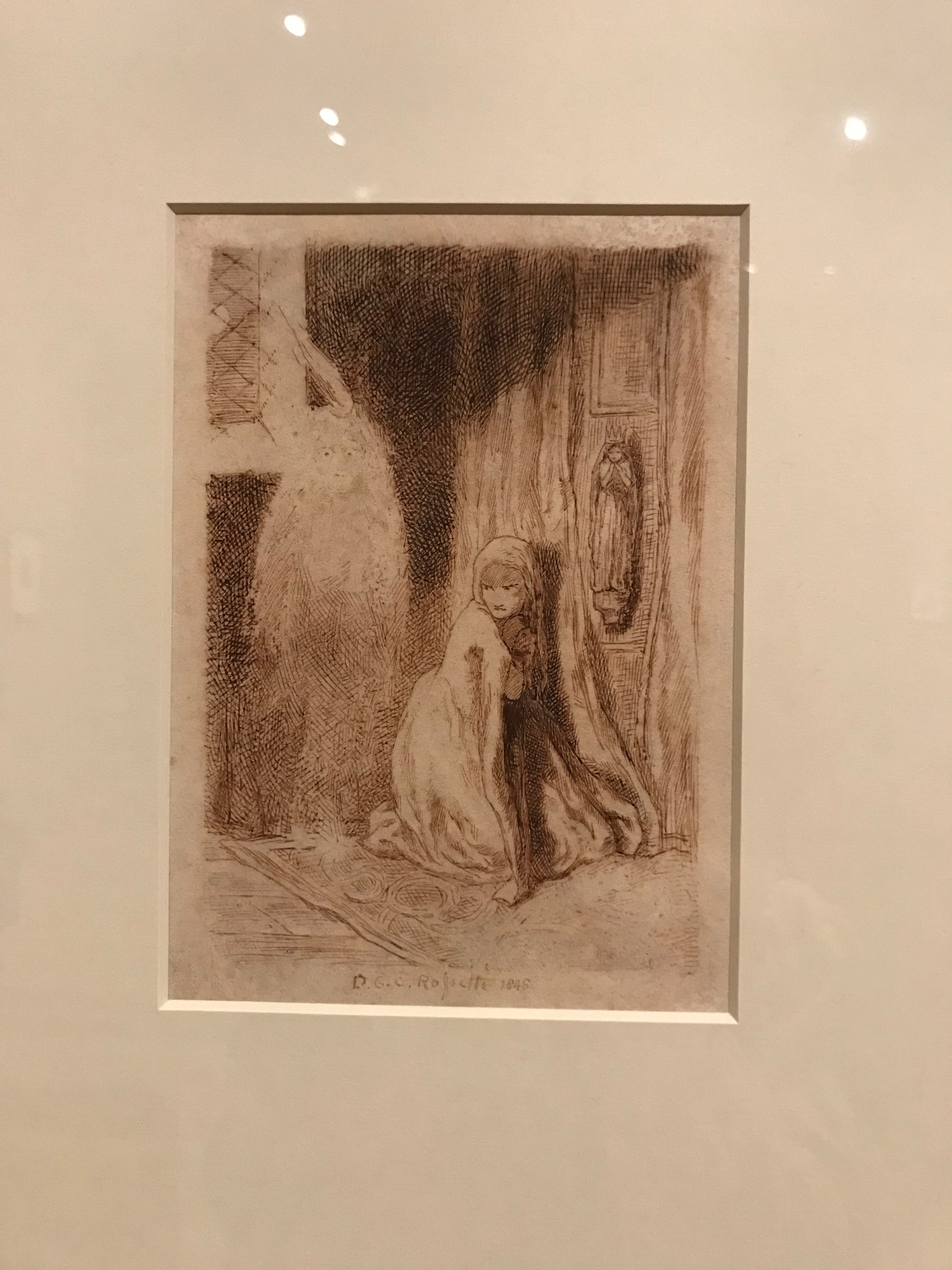

Gabriels murky drawings predating the founding of the Brotherhood in 1848 are destinctively lacking in his typictal angular style. Thank god Edgar Allen Poe’s poem the ‘Raven’ was also illustrated more successfully by Odilon Redon and Manet.

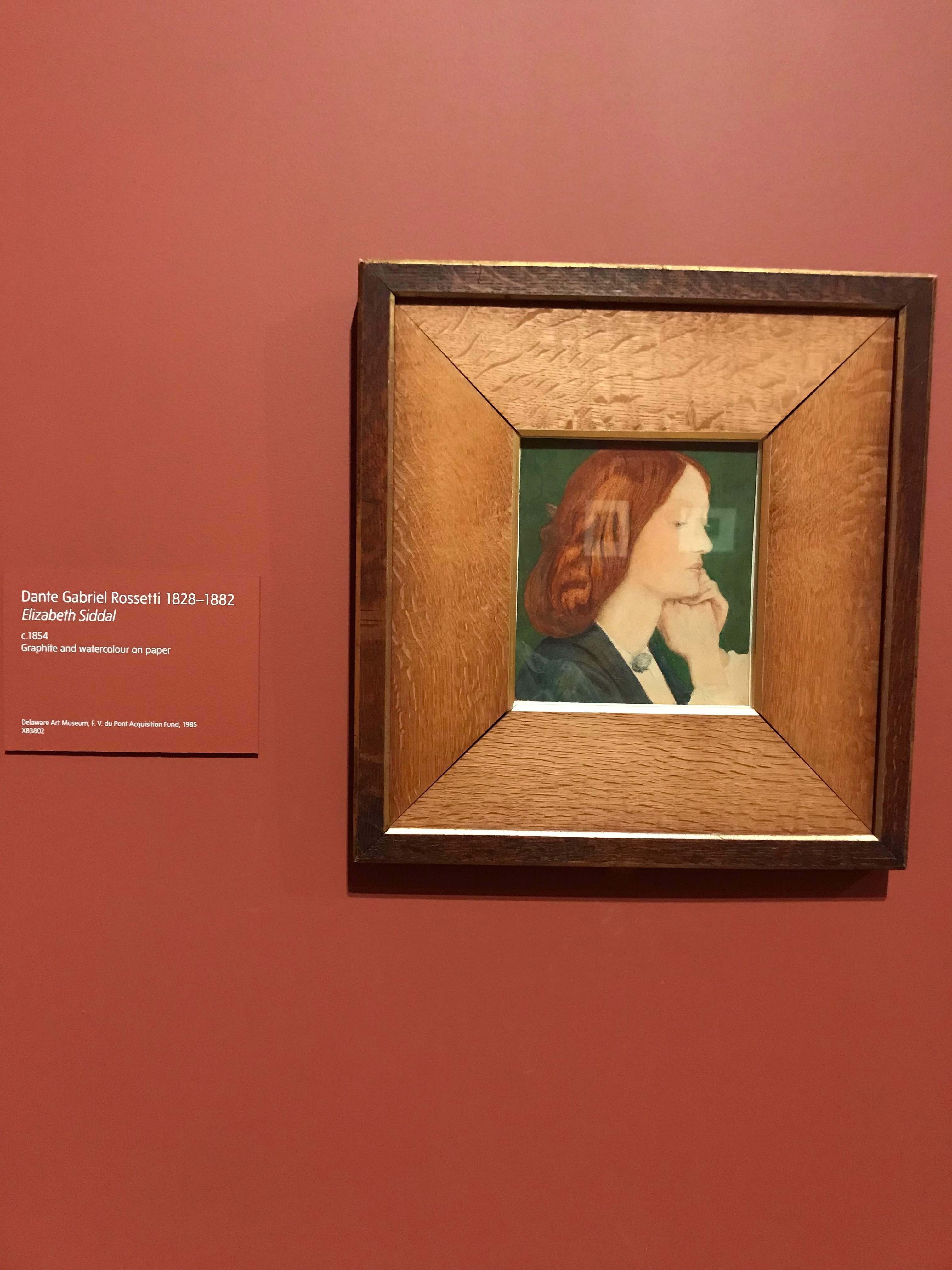

This show is tinged with the idealist fantasies of Dante Gabriel Rossetti who focused his attention on capturing his lovers in what he perceived as the ‘new modern beauty’. While these ladies were working-class class women, it felt that DG emptied them of their true identities, refusing to draw them freshly from life. Instead the models haunt the work, stripped of their character and transfigured to elign with the artist’s relish for Victoriana aesthetics. His character is often less than respectable when you consider the myth he influenced his own wife to become; a pallid phantom of his artworks. Whilst she struggled with drug use, poor health and psychological distress, Dante ruminated on her image. For an artist praised for his desire to create art which was closer to nature, these pieces feel incredibly overworked and depict worlds far away from his models’ realities. For this reason, the exhibitions vision of a social-feminist critique felt as aneamic as the image of Siddel’s Ophelia alter-ego.

While Siddel is renowned for being John Everett Millais’s muse, a positive of the exhibition was that it highlighted her rare surviving watercolours and drawings. It’s a shame this is drowned out by Dante’spresence and only her 30 paintings attest she was more than a eroticised figment of his imagination - a small repertoire due to her premature death at the age of 32. These dreamy, watercolours hint that she was more than simply a Pre-Rapahelite muse, yet her artistry is only presented within the context of her husband. She would be turning in her grave at the knowledge of this exhibition’s praise of her husbands radicalism if the Highgate Cemetery in which she rested wasn’t opened and exhumed on request of her lover to retrieve his writings a few years after her burial.

Realities are masked under a blanket of the Pre-Raphealite Brotherhood’s vivid dreams and medieval inspired fantasy. The grandiose portraits are festooned by Dante’s trance. At least William Morris was a visionary - a break from this reverie - who was fully engaged with the issues of his day. As the precurser of the Arts and Crafts movement, founding the cooperative design company, with Gabriel and others, which would become the family firm Morris and Co. Unfortunately Morris ardently fought the socialist battles whilst behind the enchanting wallpaper GD was busy shagging and painting his wife, Jane Morris. Morris convicted that the overthrow of capitalism could liberate humanity, meanwhile the secret affair involving his wife saw Jane become another trapped within her obsessive lover’s canvases; she became just another essential part of Dante’s regressive sexual boastings. Considering the pre-Raphelite stimulus seemed to always be a nameless girl, the shows preoccupation with a revolutionary narrative applied largely to a retrospective of Dante conceals the real trailblaizers of the group, Christina and Liz.