Philip Guston

Tate Modern - Bankside

25 February 2024

By Estelle Simpson

A modern man with a Renaissance ambition from youth which burgeoned into the grit to approach the depths of evil residing within the vicinity of mankind. A tenacious spirit equally laden with trauma, plus the tragic loss of his father - a figure he did not discuss very much for understandable reasons - foreseeing an upbringing tormented with layers of tragedy. This deep experience of anguish was eventually woven into the gutsy paintings he produced; an oeuvre provoked of an urgent assuaging nature. Perhaps his constant reinvention of style throughout his practice is reflective of the way he dealt with the personal tragedy he experienced, choosing to change his name and evolve his character in pursuit of the elusive ‘American dream’ the country he moved to offered. In later paintings, this repressed, weighty baggage can be seen to reemerge in the cluttered imagery dumped into the compositions. To the same degree the subject matter constitutes the rubble of America that forces its way into the work of a man with an extreme political conscience. The disturbing imagery deposited onto the canvas proved to provide relief once imparted. Guston’s unstoppable production of work was powered by the urge to find an unreachable solace in the despicable world.

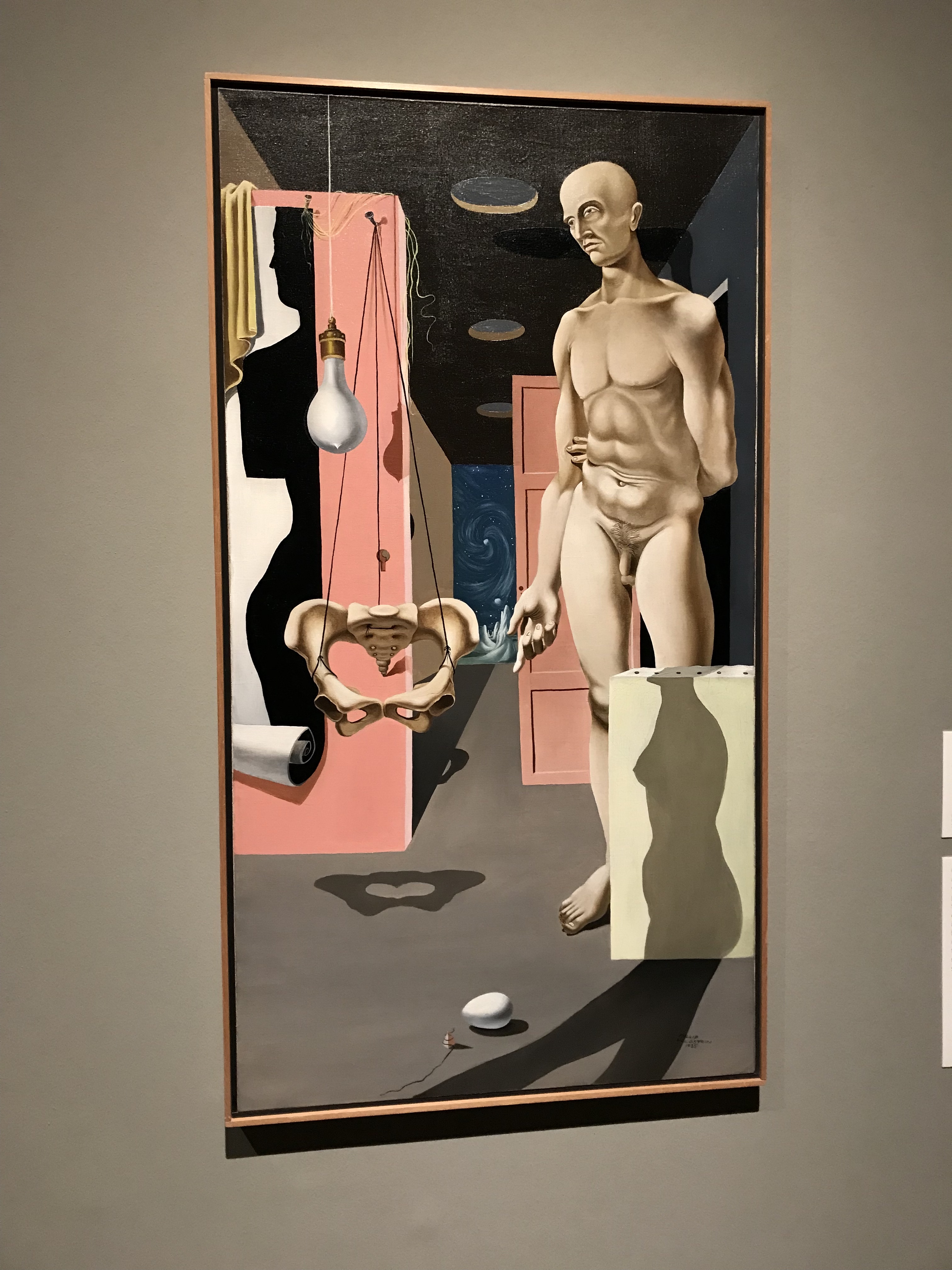

A story of a soul taxed with tragedy, a painter born of a distressing generation, and mind all encompassed by his one artistic pursuit. Guston’s style seems to have stemmed from a synergy of an early obsession for cartooning, whilst drawing on his Renaissance heroes - Michelangelo, Masaccio, and Pierra del Francesca. I enjoyed seeing the element of surrealism reminiscent of de Chirico in his early easel pieces, a movement engaged in the absurdity identified in Guston’s later work. He was daring both in the proximity to evil he engaged with in his visual universe and also transformative in his artistic trajectory. While a heavy user of his vices, Guston’s main relief seemed to be painting which signified for him a relentless search for the solace which the art form appeared to offer. This tale ends with a peachy pink plot twist - Guston reaches a stage of soft hued canvases in which self-portraits mirror a large worried head, all forehead wrinkled and wide Cyclops eyes. This is adjoined by household objects swollen to menacing proportions, and puffy KKK men performing activities not unusual to their creator’s life; painting, staring down a bottle of alcohol, or smoking a cigarette. The imagery is a mirror of the way evil routes itself in the everyday, infecting even the normalities of life. Instead of lurking beneath the surface, in Guston’s works this grimace inhabiting the quotidian exists freely and confrontationally, unmasked to a disgustingly benign degree. The works reveal a man restless and troubled by his awareness of this.

Surrounded by peers such as Pollock and de Kooning, whilst being based in New York, it is not surprising to see Guston’s leap into abstraction considering the 1960’s environment he was in. This may have seemed unforeseen considering his early easel paintings clearly metabolised an influence of the Italian Renaissance. Yet, after finding ‘what to paint’ in early work, Guston’s endeavour into abstraction was driven by an urge to figure out the ‘how’. Prior to the unexpected transition, Guston was enabled to enjoy the government’s support of Public art during the Great Depression. The exhibition demonstrated films of the gigantic Frescoes which show that while Guston was forward thinking and politically aware, he was also compelled by Master’s of painting past. He experienced incredible fortune during this time, seeing many of his fellow artist’s facilitated to make more daring and large work through being nurtured by the projects and mural competitions in New York. Public art commissions complemented Guston’s desires, allowing him to exercise an addressing of issues that spoke to people by aiding a scale of murals which were for everyone.

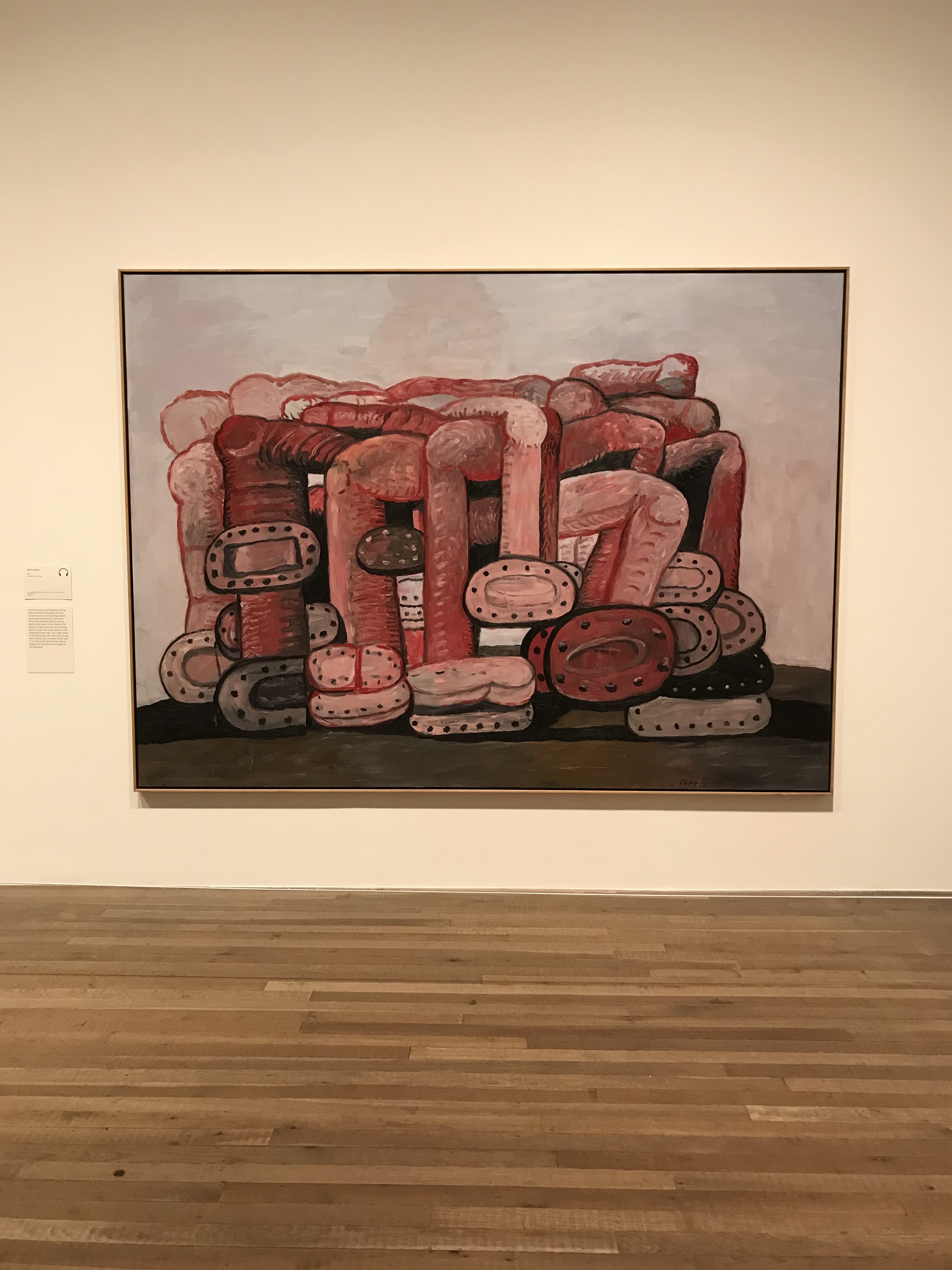

Rejecting the contrived, contained or calculated, an absolutely authentic will emerges from the idiosyncratic work. Operating amidst the disruptive period, paintings born from the hauntings of the reality which surrounded him. Despite his return to figuration disrupting the progression his critics expected to see, Guston hastily continued to trust his conscious in rejection of their reproval. This bold shift back to figuratism finally crystallised into was that cartoon-like, slightly coarse style, rendered as caricature - a union of preceding styles. The dualism completely evolved, offering sobering images summoning baggage, disorder and psychological weight to the figure, investing it with political and conceptual dimensions that were grim to describe. He also invested the physicality of ordinary objects with the weight of daily headlines. Paintings revealed the casualness of racialised violence and are products of the artist’s rumination on the systems of repression that flow through our cities, schools, halls of government, museums and studios. Pieces were so powerfully disturbing that they continued to cause disgrace in contemporary audiences, even causing the Tate show to be delayed; this goading evidences the dangerous proximity he had taken towards evil in this return to representation. Fears of the institution reflected little faith in its viewership being able to ascertain it was not racism.

“If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago

My favourite piece ‘Couple in Bed’ bristles with unease, made during a time when Guston and his wife were more physically frail; it is considered one of his most intimate and revealing works. A quivering clutch of paint brushes is observed as he lays in the safety of bed with his wife. This poignant image is a rare place of peace, showing devotion and achievment, whilst not forgetting the horror which continues to make the figure tremble in bed. Painterly work of this period was hoods off, of a nature that was more overtly autobiographical. The tender imagery of this piece excites me. A back brace for a painting - an element used for holding a stretcher bar structure in place - lays within the bedsheets covering the couples embrace. This is an extraordinary visual subject to represent his celebration of the power he percieved in their bond. In view of Guston’s struggle in his value for both painting and his love life, it seems the debilitating effects of age brought a renewed significance to his relationship. While violence erupts outside, this piece portrays that which is inside his domestic life. His temperament was sometimes fiery and his bursts of anger considerable, a passion at least exerted into art which he had a highly emotional and personal relationship with. Guston not only risked his art-world standing and livelihood in his honest, obsessional painting pursuit, but also compromised family life. However, this piece demonstrates a deep appreciation in the committed role his wife played as a someone close to him who tolerated his unshakable artistic activity.

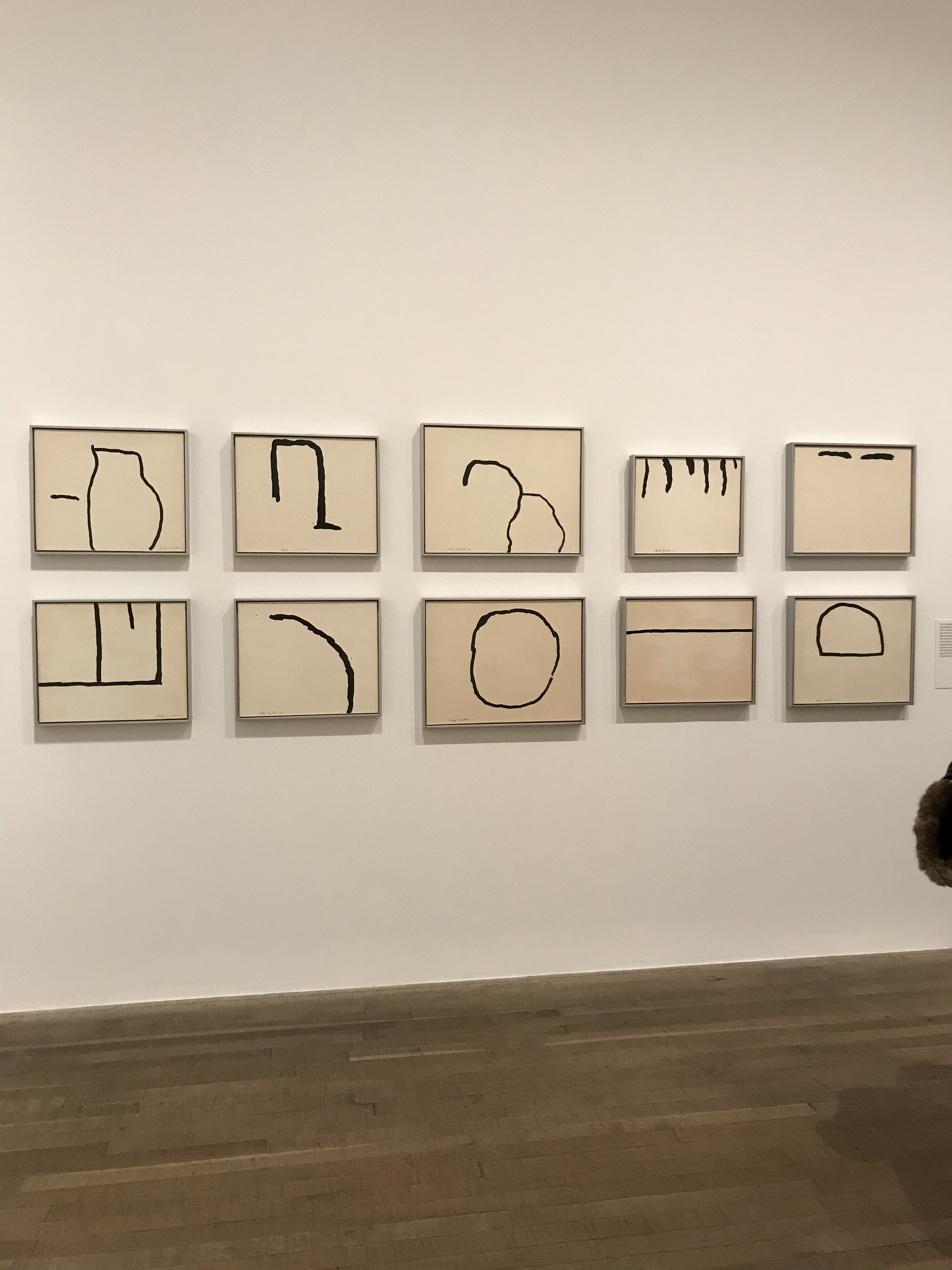

Guston maintained a ‘Not for Sale’ collection throughout his career, made up of reference paintings which materialised from a process of creating several pieces in order to achieve his exact vision. While his paintings grew inevitably more grotesuqe through the 1970’s, Guston was always seeking to reemerge anew from the meagre, damaged legacy he began with. Forever in pursuit of his ‘true identity’, Guston maintained an existentialist philosophy throughout his career. He even propelled his creativity by incessant drawing during years long breaks from painting, in ceaseless ambition which began with learning how to make a painting and then teaching himself how to unmake one. Self doubt and questioning was personally admitted as crucial to his creative process. He believed that by conjouring from painterly incident he could both indentify and defy the intrinsic parameters of the support and materials. Guston’s ensuing choice in cartoon imagery allowed him to evoke recognisable objects in a fundamentally paradoxical way due to their absurdity. The paintings later are a marriage of the ludicrous and compelling. Striking images that embody the dilemma and accomodate the doubt.