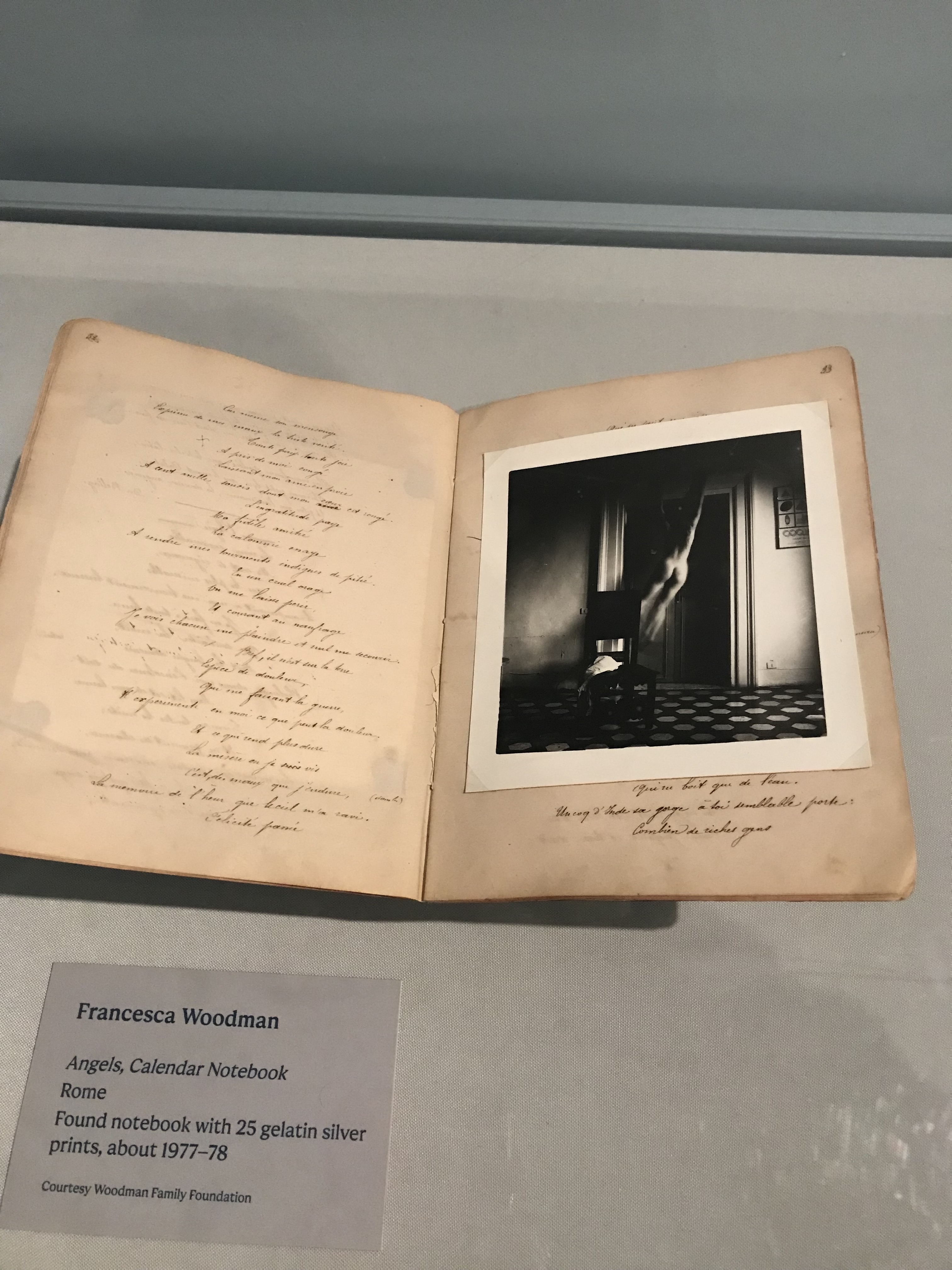

Francesca Woodman, Portraits to Dream In

The National Portrait Gallery

Until June 16, 2024

An essay by Estelle Simpson

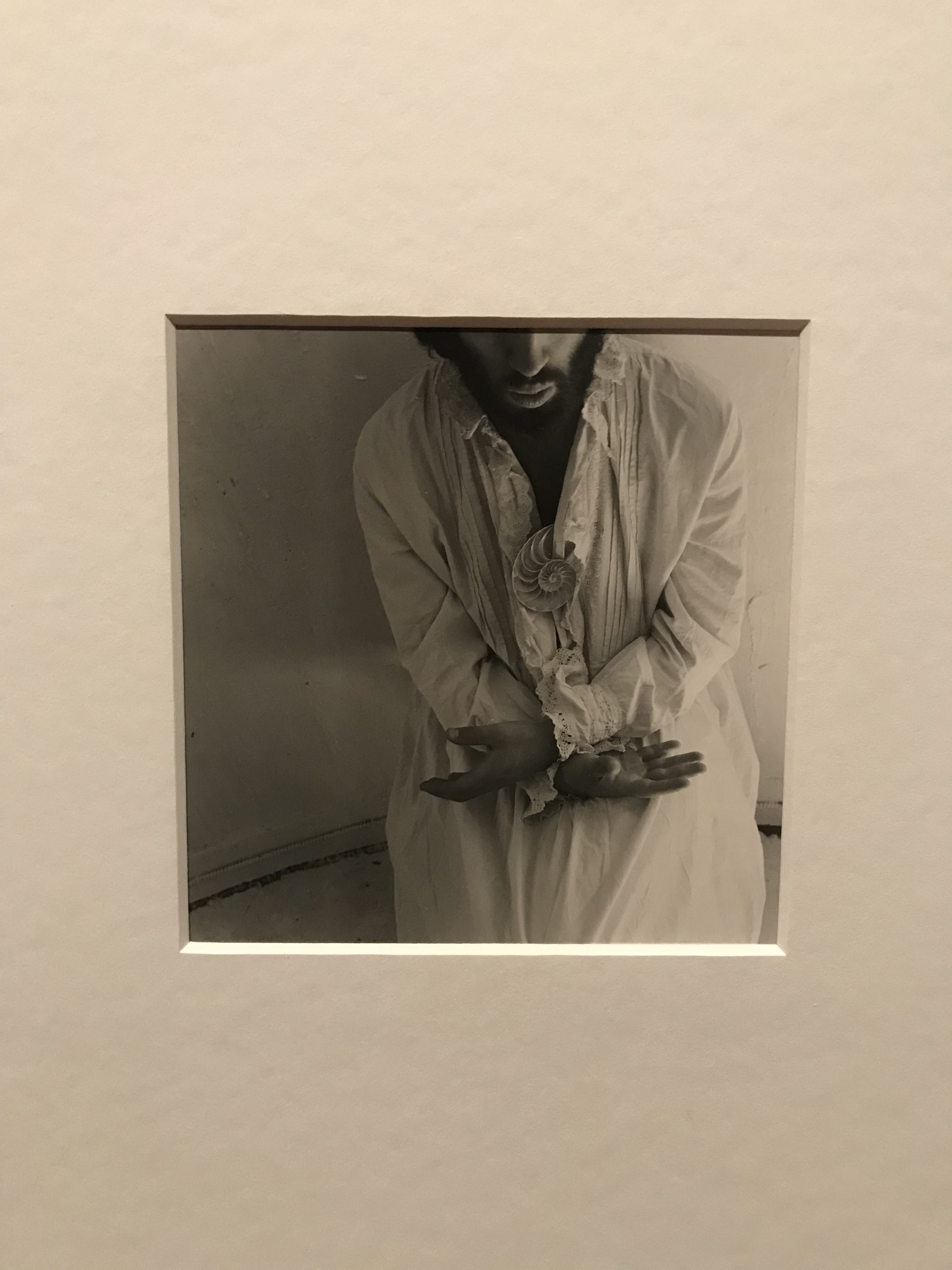

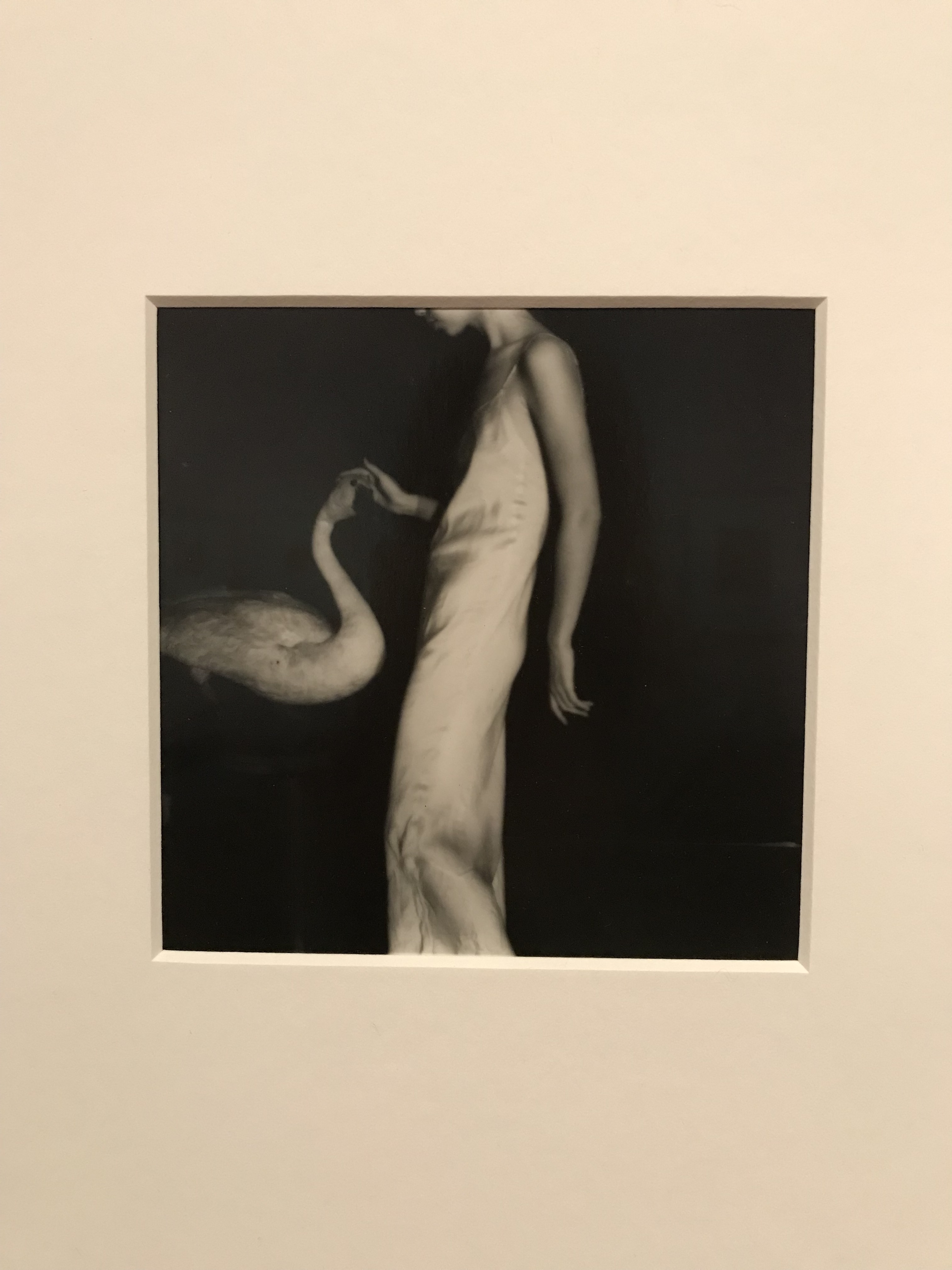

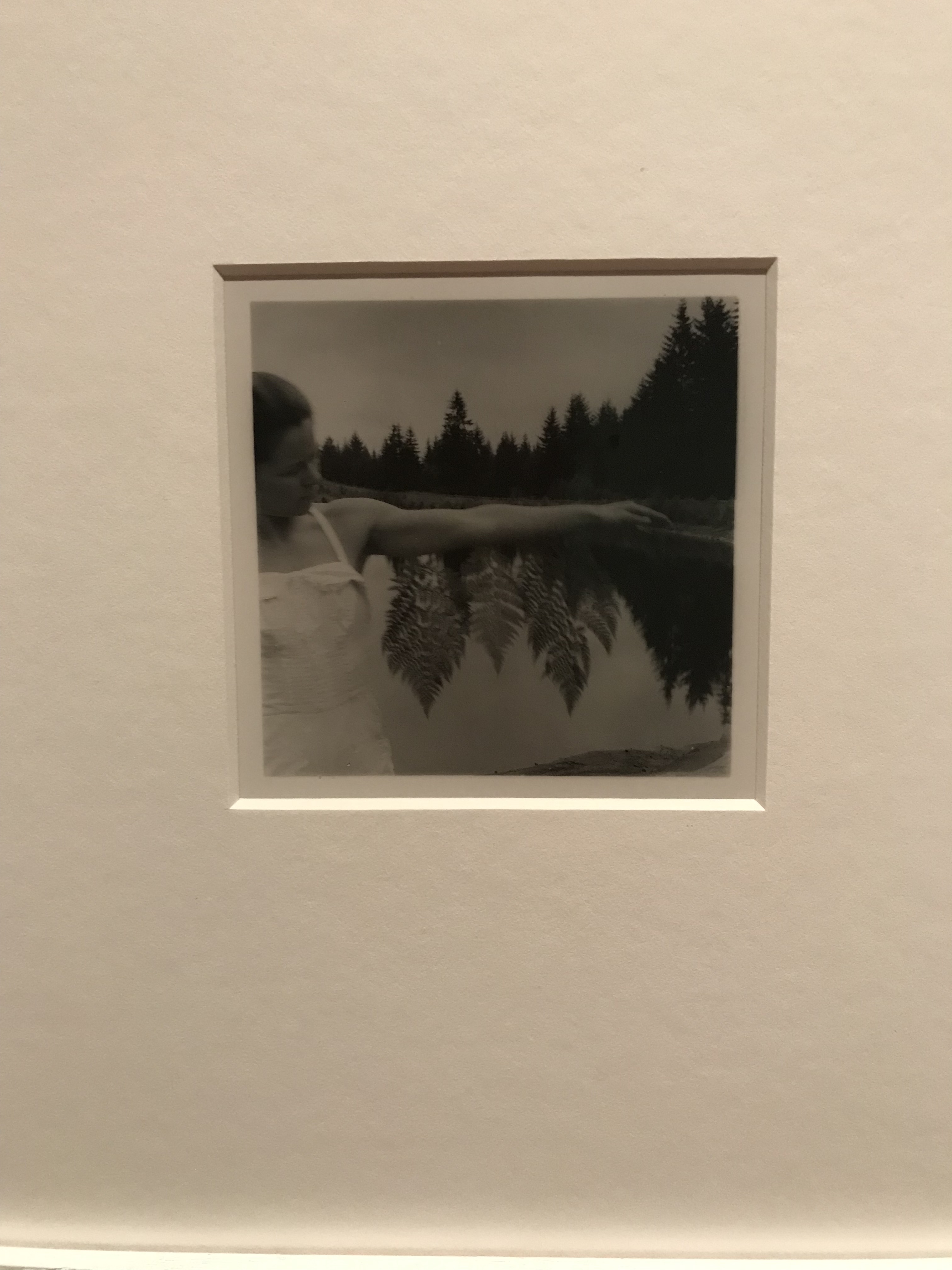

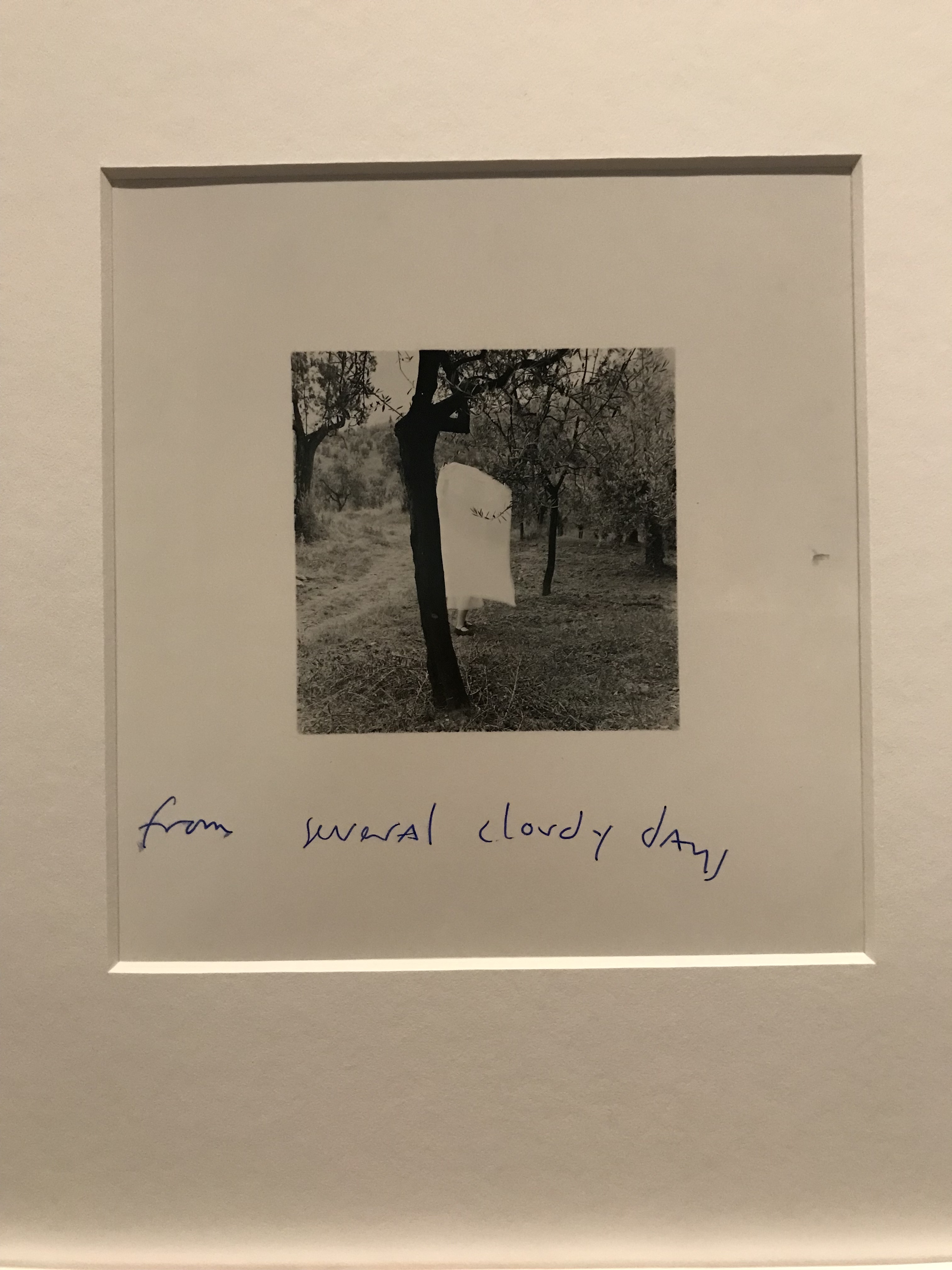

I’d like to share an artist who inspires me despite my usual disinterest in photography. For me, Francesca Woodman’s work transcends what usually limits the medium to constraints of reality. Of course, surrealism is possible within the photographic lens, as is shown in Man Ray’s pioneering shots. However, where Ray’s dream imagery employed glass beads, Woodman contorts reality through using her body, motion, nature, and space to enliven the artwork with tinges of mystery. The contrast lies in the domestic props and sets Woodman composed for her shoots; this artillery meant that the resulting warping’s were more subtle in their mystification of reality. Hence, Woodman managed to balance an intimate approach, achieving quite vulnerable, personal statements in what she captured - using stimuli caught directly from real, everyday life - whilst also reaching a dream-like, perplexing quality. In an impressive way, Woodman’s could select and organise things which would generally be recognisable within the everyday lexicon and, at the same time, create a photograph that blurs all senses of materiality. This deftly demonstrates the way an uncertain, tormented mind struggles to make sense of reality, making for an evocative catalogue of work that spans 9 years.

Like many surrealists, she would combine the familiar in unfamiliar contexts to evoke uncanny feelings. Yet, what her predecessors of the self-portrait Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini were able to realize in paintwork which allowed any imagined subject to be materialised, Woodman was able to use her camera to infuse surrealist agency. Claude Cahun is obviously a great artistic predecessor of Woodman, yet the latter’s commitment to the domestic setting makes her pieces feel less performative and theatrical as much surrealist language can feel. The chilling atmosphere projected onto domesticity makes the emotion in these works feel much less staged and this candid intrigue makes her vision feel extremely genuine.

Often it feels the analysis of Woodman’s work is trapped by the contextualisation of her death. However, her photographs should not be read as simply indications of psychological torment. As these works in the show display, there are themes of beauty, symbolism, transformation, and storytelling that hold great leverage in readings of the work. The evocative portrait photography should be examined for its profound notions. Both driven by hysteria and reflective in nature, the world Woodman suggests invites a pondering of the complexities of self-representation and identity.

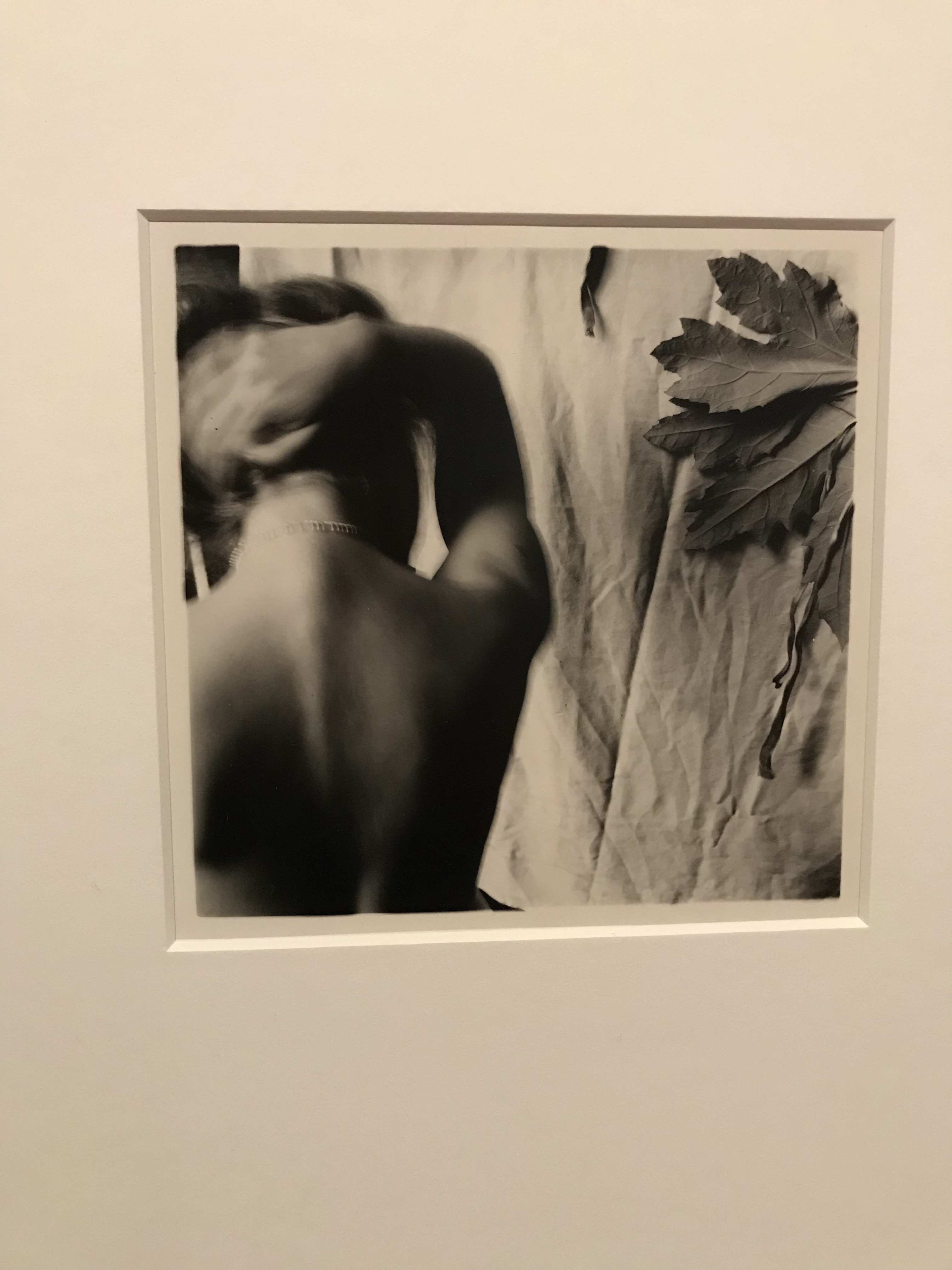

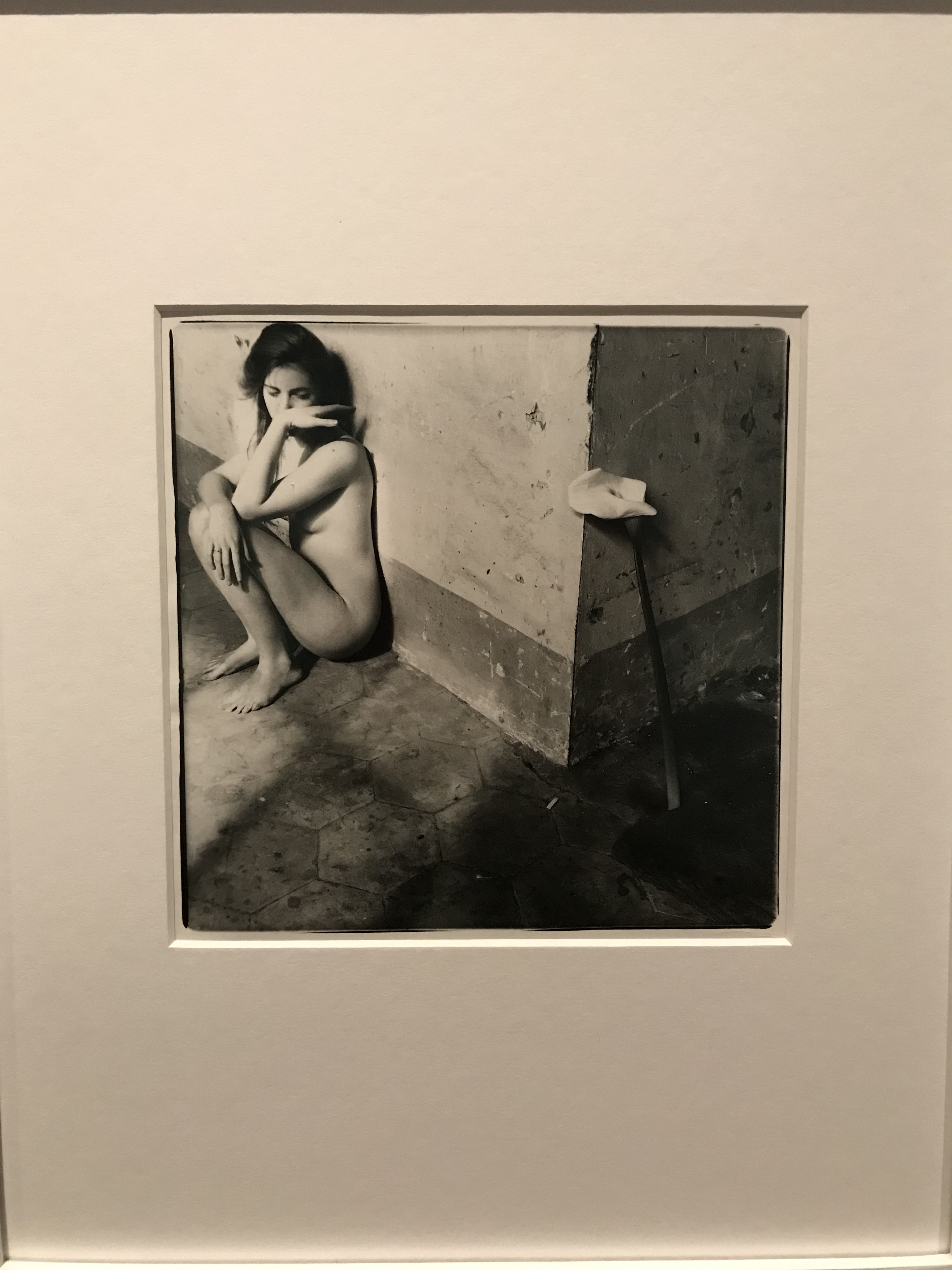

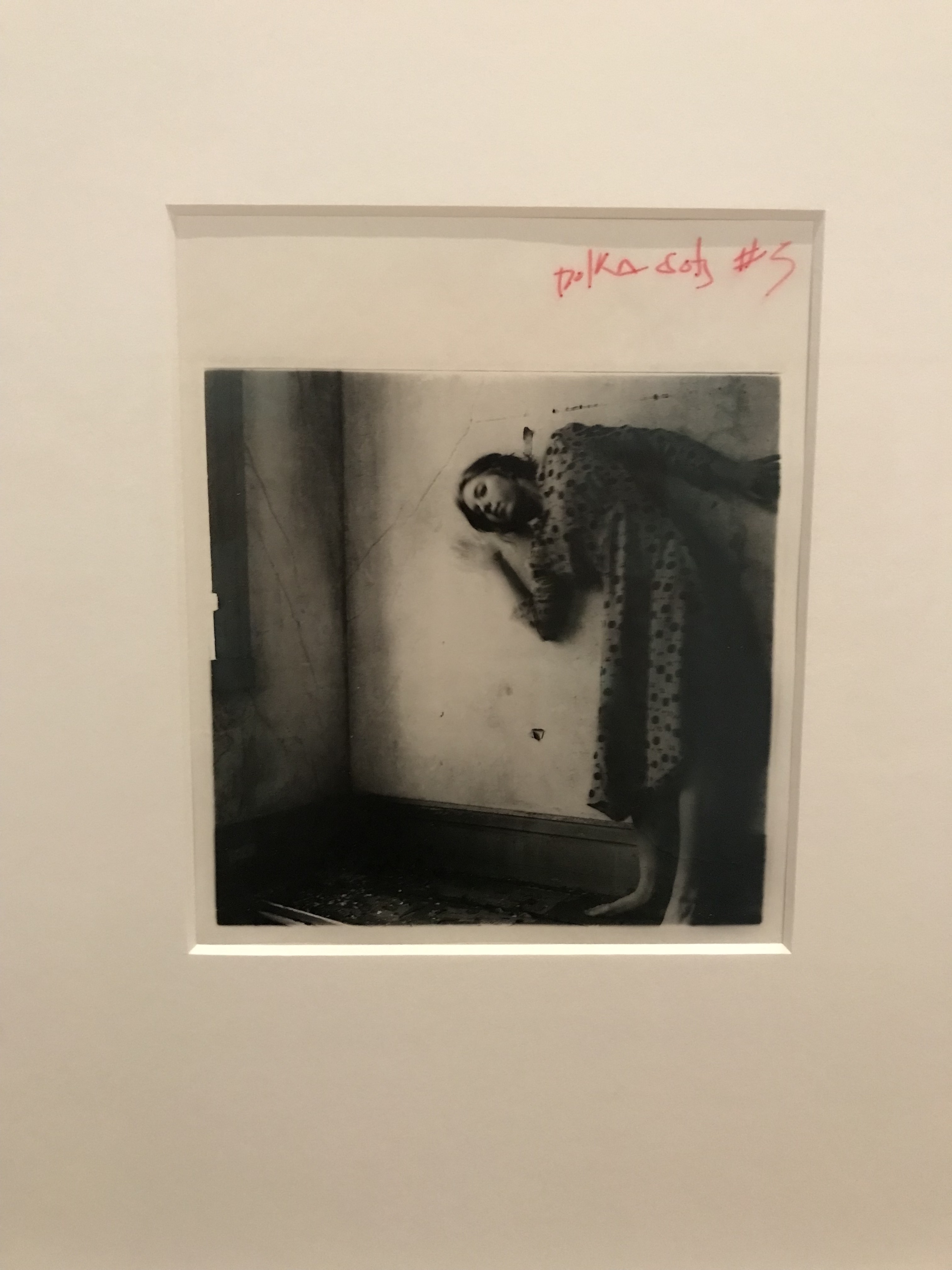

In Woodman’s hands, the photograph demonstrates how the body and architecture share essentially compelling aspects with one another. The continuity in the aesthetics of interior spaces Woodman combined with the body was a means of aligning the body with these environments. For instance, ‘Polka Dots 5’ shows the body leant against a wall, a composition decision that suggests the ability to move through a solid surface and there is delicate blurring where the body touches the wall behind it. Furthermore, the crumbling and cracked plaster of the wall reveals themes of fragility and peeling back, implying the idea of the positive and negative (black and white). She is presented merging with the wall of an abandoned house; there is a brutality to the images in which you cannot decipher whether the elusive body is trapped or liberated.

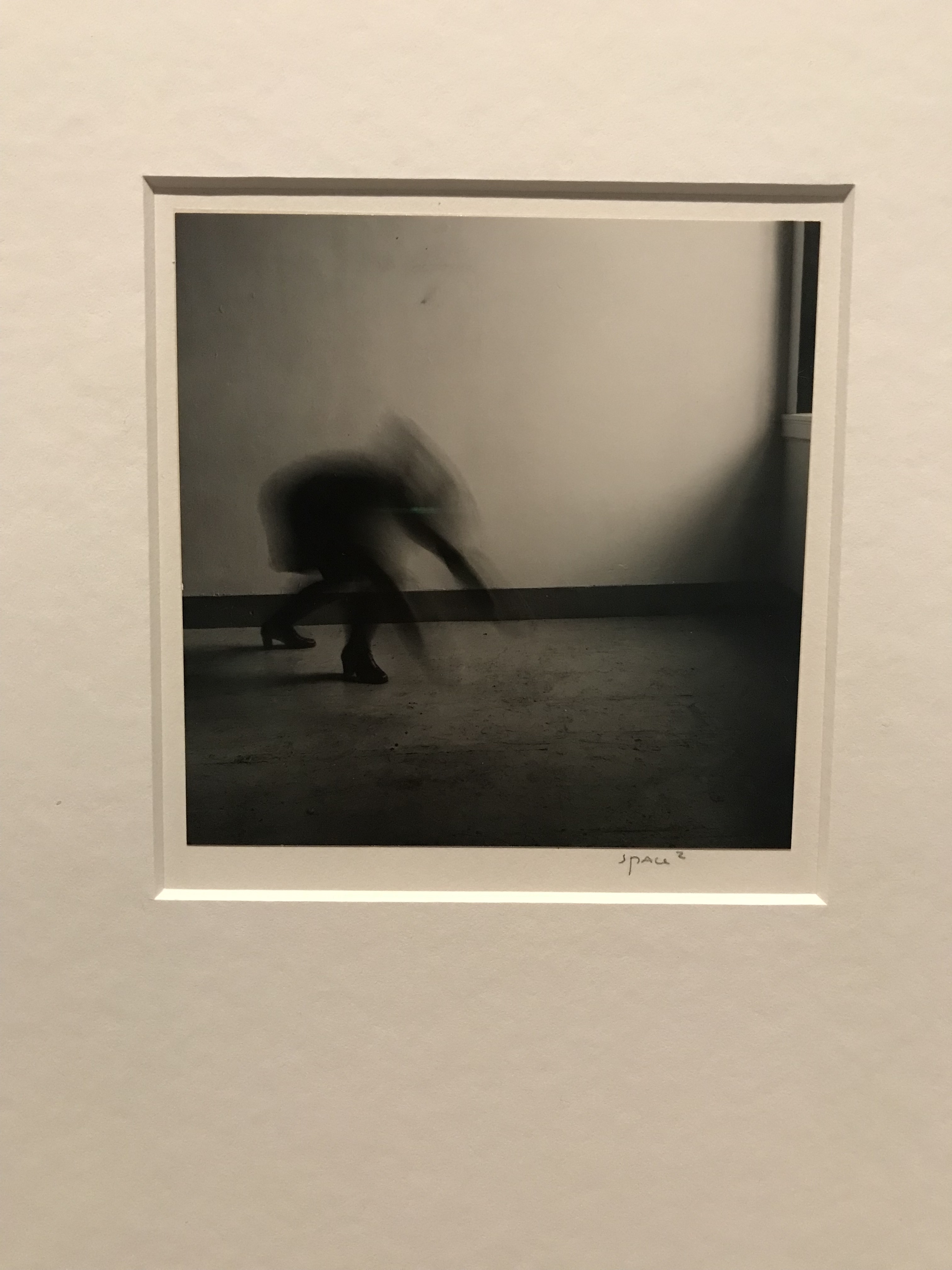

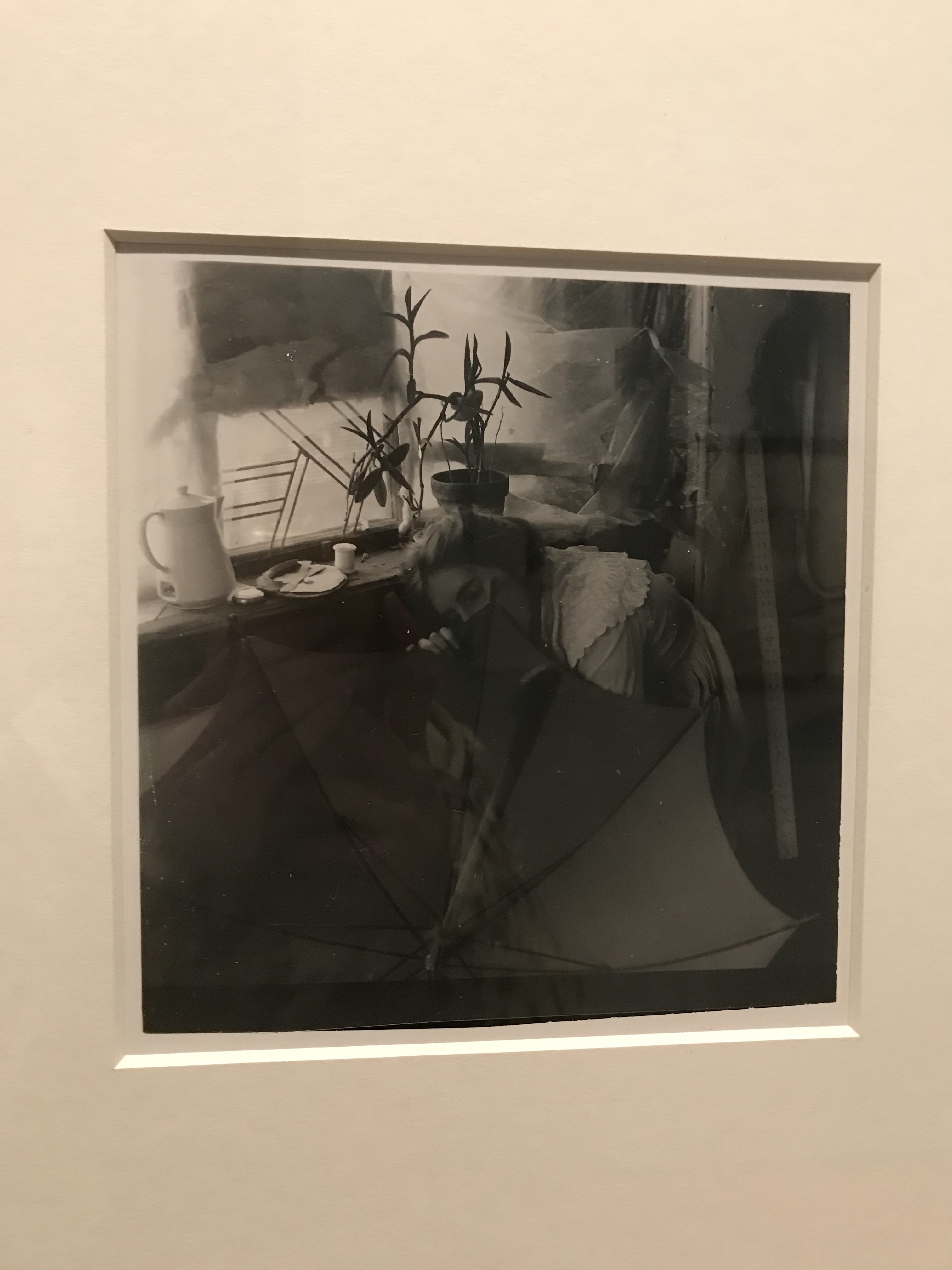

Fused in this testing of the relation of the body and architectural space is also the expression resulting from the manipulation of the camera itself. Long exposures and double exposures further manipulate appearances so that there is a sense of ephemerality as the recurring subject of the body seems to be escaping the viewer’s gaze. This trio of the body, architecture and camera impression become a synergy that test figure-spatial boundaries. The technique, landscape, and body are suggested traversing and dissolving, so that everything seems to be in a heightened state of change and decay, and this fleeting sense refuses her body to be defined by the viewer. Not only does her body seem to dissolve into the surrounding space, but that space is also in a process of dissolution.

Cryptic use of ordinary objects further excites insights into Woodman’s practice. A selection of her surreal scenes shown in this show were also combined with the simple use of a conventional mirror, employed to make delicate observations on touch and separation. The doubling that forms part of her exploration of composition in her photographs of the period 1979-1980 complicates the idea of self-portraiture by proposing the idea of the body double or stand in. Layered by reflections within the mirrors frame, her subject’s body is fused with others; two figures are composed like pieces of a puzzle. This creates a subtle rhythm of balance implying a supportive connection between female muses.

Her artistic vision conjured an enigmatic dream-state, as she indicated, the photographs could be ‘places for the viewer to dream in.’ Many of the works in this exhibition were very recognisable to me, yet this is a testament to how unforgettable her photographs are due to their arresting nature. There seems to be a timeless immediacy created by her meditations on the transient experience of being in the body.